Finite element basis functions (1)¶

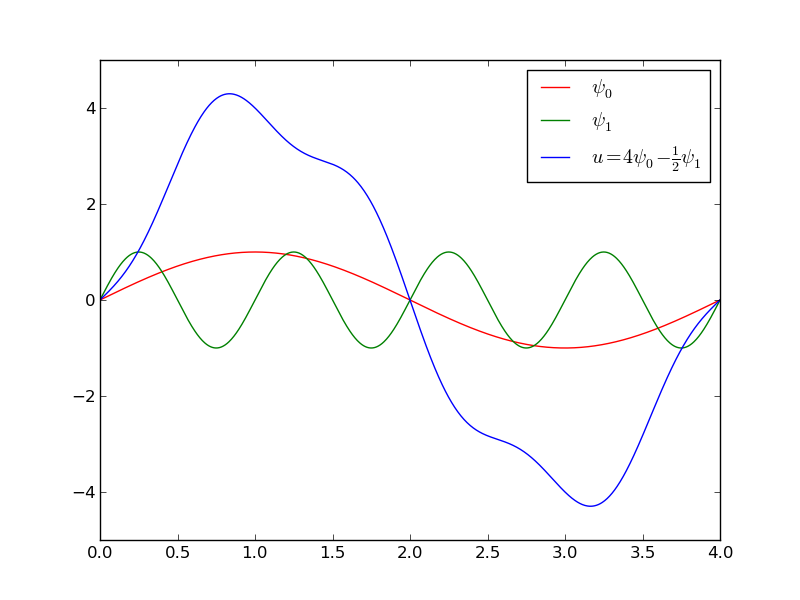

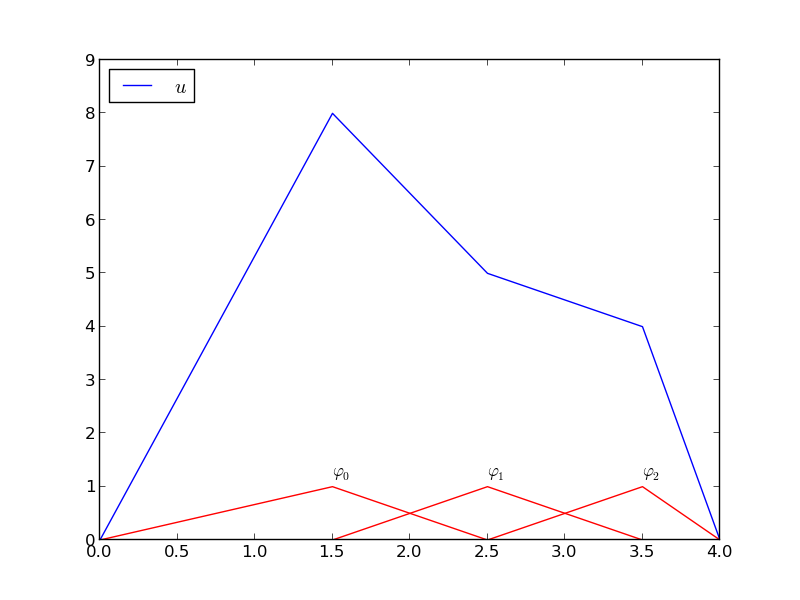

The specific basis functions exemplified in the section Approximation of functions are in general nonzero on the entire domain \(\Omega\), see Figure A function resulting from adding two sine basis functions for an example where we plot \(\psi_0(x)=\sin\frac{1}{2}\pi x\) and \(\psi_1(x)=\sin 2\pi x\) together with a possible sum \(u(x)=4\psi_0(x) - \frac{1}{2}\psi_1(x)\). We shall now turn the attention to basis functions that have compact support, meaning that they are nonzero on only a small portion of \(\Omega\). Moreover, we shall restrict the functions to be piecewise polynomials. This means that the domain is split into subdomains and the function is a polynomial on one or more subdomains, see Figure A function resulting from adding three local piecewise linear (hat) functions for a sketch involving locally defined hat functions that make \(u=\sum_jc_j{\psi}_j\) piecewise linear. At the boundaries between subdomains one normally forces continuity of the function only so that when connecting two polynomials from two subdomains, the derivative becomes discontinuous. These type of basis functions are fundamental in the finite element method.

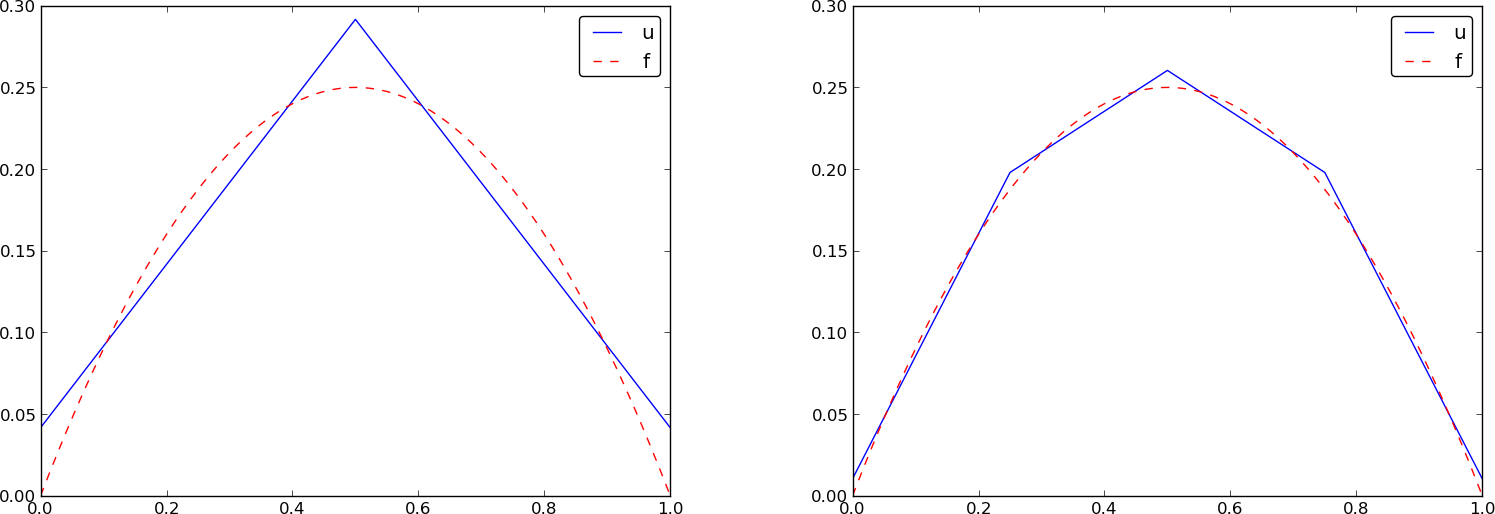

A function resulting from adding two sine basis functions

A function resulting from adding three local piecewise linear (hat) functions

We first introduce the concepts of elements and nodes in a simplistic fashion as often met in the literature. Later, we shall generalize the concept of an element, which is a necessary step to treat a wider class of approximations within the family of finite element methods. The generalization is also compatible with the concepts used in the FEniCS finite element software.

Elements and nodes¶

Let us divide the interval \(\Omega\) on which \(f\) and \(u\) are defined into non-overlapping subintervals \(\Omega^{(e)}\), \(e=0,\ldots,N_e\):

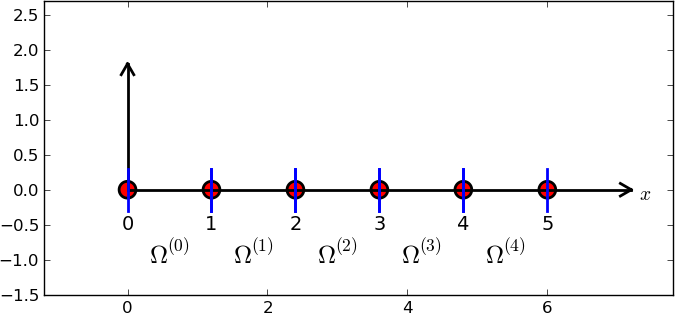

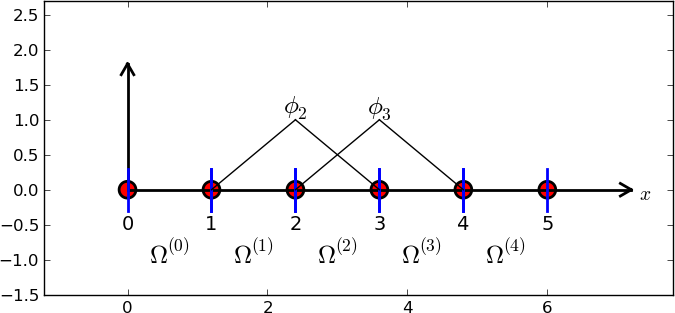

We shall for now refer to \(\Omega^{(e)}\) as an element, having number \(e\). On each element we introduce a set of points called nodes. For now we assume that the nodes are uniformly spaced throughout the element and that the boundary points of the elements are also nodes. The nodes are given numbers both within an element and in the global domain. These are referred to as local and global node numbers, respectively. Figure Finite element mesh with 5 elements and 6 nodes shows element boundaries with small vertical lines, nodes as small disks, element numbers in circles, and global node numbers under the nodes.

Finite element mesh with 5 elements and 6 nodes

Nodes and elements uniquely define a finite element mesh, which is our discrete representation of the domain in the computations. A common special case is that of a uniformly partitioned mesh where each element has the same length and the distance between nodes is constant.

Example (2)¶

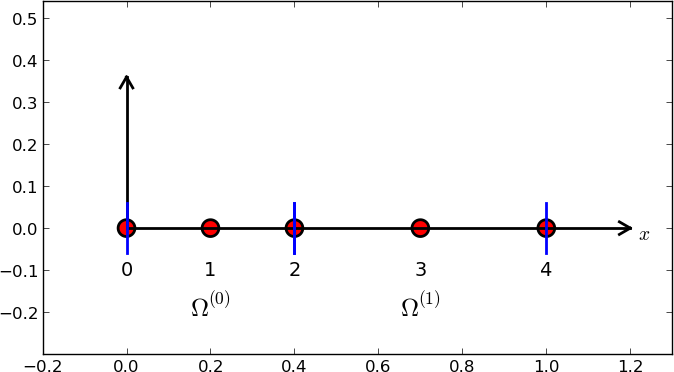

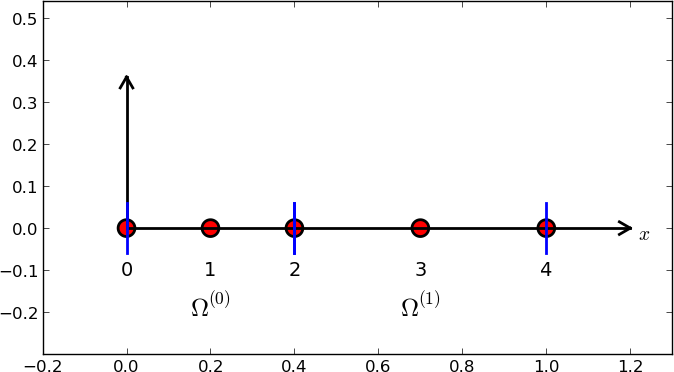

On \(\Omega =[0,1]\) we may introduce two elements, \(\Omega^{(0)}=[0,0.4]\) and \(\Omega^{(1)}=[0.4,1]\). Furthermore, let us introduce three nodes per element, equally spaced within each element. Figure Finite element mesh with 2 elements and 5 nodes shows the mesh. The three nodes in element number 0 are \(x_0=0\), \(x_1=0.2\), and \(x_2=0.4\). The local and global node numbers are here equal. In element number 1, we have the local nodes \(x_0=0.4\), \(x_1=0.7\), and \(x_2=1\) and the corresponding global nodes \(x_2=0.4\), \(x_3=0.7\), and \(x_4=1\). Note that the global node \(x_2=0.4\) is shared by the two elements.

Finite element mesh with 2 elements and 5 nodes

For the purpose of implementation, we introduce two lists or arrays: nodes for storing the coordinates of the nodes, with the global node numbers as indices, and elements for holding the global node numbers in each element, with the local node numbers as indices. The nodes and elements lists for the sample mesh above take the form

nodes = [0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.7, 1]

elements = [[0, 1, 2], [2, 3, 4]]

Looking up the coordinate of local node number 2 in element 1 is here done by nodes[elements[1][2]] (recall that nodes and elements start their numbering at 0).

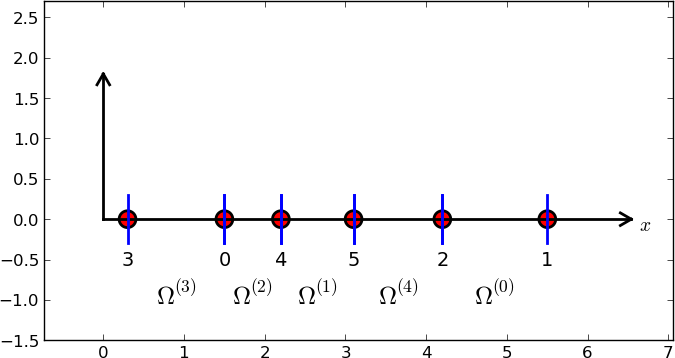

The numbering of elements and nodes does not need to be regular. Figure Example on irregular numbering of elements and nodes shows and example corresponding to

nodes = [1.5, 5.5, 4.2, 0.3, 2.2, 3.1]

elements = [[2, 1], [4, 5], [0, 4], [3, 0], [5, 2]]

Example on irregular numbering of elements and nodes

The basis functions¶

Construction principles¶

Finite element basis functions are in this text recognized by the notation \({\varphi}_i(x)\), where the index now in the beginning corresponds to a global node number. In the current approximation problem we shall simply take \({\psi}_i = {\varphi}_i\).

Let \(i\) be the global node number corresponding to local node \(r\) in element number \(e\). The finite element basis functions \({\varphi}_i\) are now defined as follows.

- If local node number \(r\) is not on the boundary of the element, take \({\varphi}_i(x)\) to be the Lagrange polynomial that is 1 at the local node number \(r\) and zero at all other nodes in the element. On all other elements, \({\varphi}_i=0\).

- If local node number \(r\) is on the boundary of the element, let \({\varphi}_i\) be made up of the Lagrange polynomial over element \(e\) that is 1 at node \(i\), combined with the Lagrange polynomial over element \(e+1\) that is also 1 at node \(i\). On all other elements, \({\varphi}_i=0\).

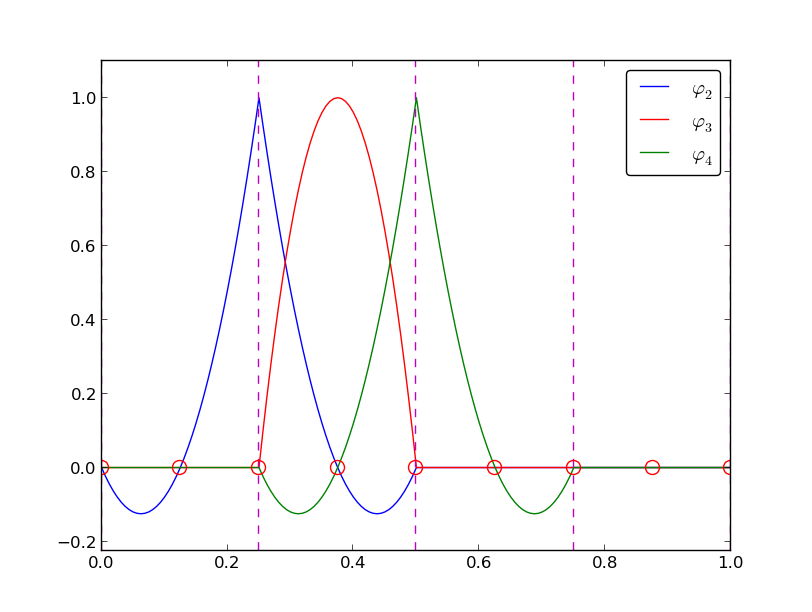

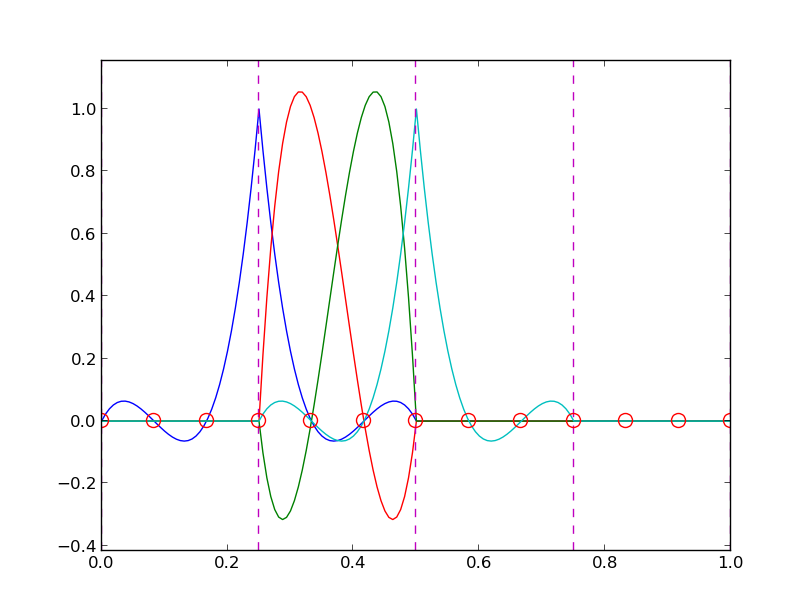

A visual impression of three such basis functions are given in Figure Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1.

Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1

Properties of \({\varphi}_i\)¶

The construction of basis functions according to the principles above lead to two important properties of \({\varphi}_i(x)\). First,

when \(x_{j}\) is a node in the mesh with global node number \(j\). The result \({\varphi}_i(x_{j}) =\delta_{ij}\) arises because the Lagrange polynomials are constructed to have exactly this property. The property also implies a convenient interpretation of \(c_i\) as the value of \(u\) at node \(i\). To show this, we expand \(u\) in the usual way as \(\sum_jc_j{\psi}_j\) and choose \({\psi}_i = {\varphi}_i\):

Because of this interpretation, the coefficient \(c_i\) is by many named \(u_i\) or \(U_i\).

Second, \({\varphi}_i(x)\) is mostly zero throughout the domain:

- \({\varphi}_i(x) \neq 0\) only on those elements that contain global node \(i\),

- \({\varphi}_i(x){\varphi}_j(x) \neq 0\) if and only if \(i\) and \(j\) are global node numbers in the same element.

Since \(A_{i,j}\) is the integral of \({\varphi}_i{\varphi}_j\) it means that most of the elements in the coefficient matrix will be zero. We will come back to these properties and use them actively in computations to save memory and CPU time.

We let each element have \(d+1\) nodes, resulting in local Lagrange polynomials of degree \(d\). It is not a requirement to have the same \(d\) value in each element, but for now we will assume so.

Example on piecewise quadratic finite element functions¶

Figure Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1 illustrates how piecewise quadratic basis functions can look like (\(d=2\)). We work with the domain \(\Omega = [0,1]\) divided into four equal-sized elements, each having three nodes. The nodes and elements lists in this particular example become

nodes = [0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.875, 1.0]

elements = [[0, 1, 2], [2, 3, 4], [4, 5, 6], [6, 7, 8]]

Figure Sketch of mesh with 4 elements and 3 nodes per element sketches the mesh and the numbering. Nodes are marked with circles on the \(x\) axis and element boundaries are marked with vertical dashed lines in Figure Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1.

Sketch of mesh with 4 elements and 3 nodes per element

Let us explain in detail how the basis functions are constructed according to the principles. Consider element number 1 in Figure Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1, \(\Omega^{(1)}=[0.25, 0.5]\), with local nodes 0, 1, and 2 corresponding to global nodes 2, 3, and 4. The coordinates of these nodes are \(0.25\), \(0.375\), and \(0.5\), respectively. We define three Lagrange polynomials on this element:

- The polynomial that is 1 at local node 1 (\(x=0.375\), global node 3) makes up the basis function \({\varphi}_3(x)\) over this element, with \({\varphi}_3(x)=0\) outside the element.

- The Lagrange polynomial that is 1 at local node 0 is the “right part” of the global basis function \({\varphi}_2(x)\). The “left part” of \({\varphi}_2(x)\) consists of a Lagrange polynomial associated with local node 2 in the neighboring element \(\Omega^{(0)}=[0, 0.25]\).

- Finally, the polynomial that is 1 at local node 2 (global node 4) is the “left part” of the global basis function \({\varphi}_4(x)\). The “right part” comes from the Lagrange polynomial that is 1 at local node 0 in the neighboring element \(\Omega^{(2)}=[0.5, 0.75]\).

As mentioned earlier, any global basis function \({\varphi}_i(x)\) is zero on elements that do not contain the node with global node number \(i\).

The other global functions associated with internal nodes, \({\varphi}_1\), \({\varphi}_5\), and \({\varphi}_7\), are all of the same shape as the drawn \({\varphi}_3\), while the global basis functions associated with shared nodes also have the same shape, provided the elements are of the same length.

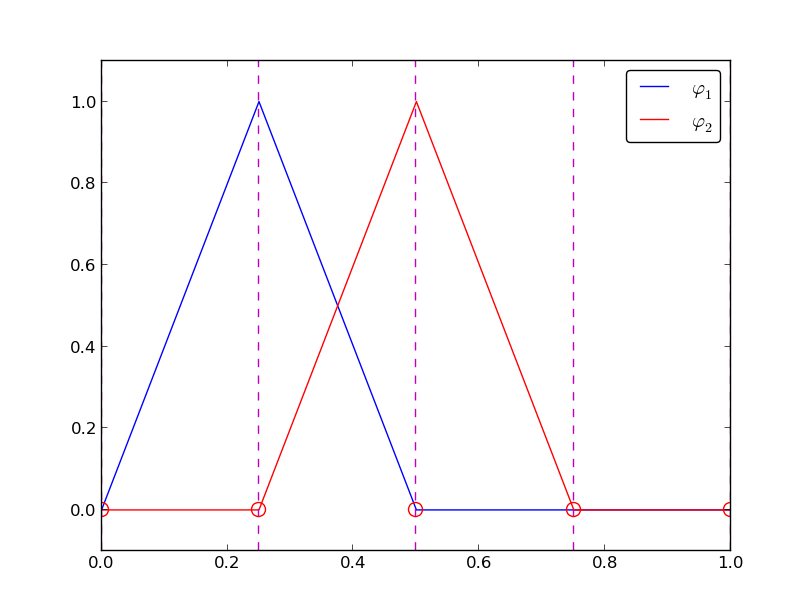

Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions associated with nodes in element 1

Example on piecewise linear finite element functions¶

Figure Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions associated with nodes in element 1 shows piecewise linear basis functions (\(d=1\)). Also here we have four elements on \(\Omega = [0,1]\). Consider the element \(\Omega^{(1)}=[0.25,0.5]\). Now there are no internal nodes in the elements so that all basis functions are associated with nodes at the element boundaries and hence made up of two Lagrange polynomials from neighboring elements. For example, \({\varphi}_1(x)\) results from the Lagrange polynomial in element 0 that is 1 at local node 1 and 0 at local node 0, combined with the Lagrange polynomial in element 1 that is 1 at local node 0 and 0 at local node 1. The other basis functions are constructed similarly.

Explicit mathematical formulas are needed for \({\varphi}_i(x)\) in computations. In the piecewise linear case, one can show that

Here, \(x_{j}\), \(j=i-1,i,i+1\), denotes the coordinate of node \(j\). For elements of equal length \(h\) the formulas can be simplified to

Example on piecewise cubic finite element basis functions¶

Piecewise cubic basis functions can be defined by introducing four nodes per element. Figure Illustration of the piecewise cubic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1 shows examples on \({\varphi}_i(x)\), \(i=3,4,5,6\), associated with element number 1. Note that \({\varphi}_4\) and \({\varphi}_5\) are nonzero on element number 1, while \({\varphi}_3\) and \({\varphi}_6\) are made up of Lagrange polynomials on two neighboring elements.

Illustration of the piecewise cubic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1

We see that all the piecewise linear basis functions have the same “hat” shape. They are naturally referred to as hat functions, also called chapeau functions. The piecewise quadratic functions in Figure Illustration of the piecewise quadratic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1 are seen to be of two types. “Rounded hats” associated with internal nodes in the elements and some more “sombrero” shaped hats associated with element boundary nodes. Higher-order basis functions also have hat-like shapes, but the functions have pronounced oscillations in addition, as illustrated in Figure Illustration of the piecewise cubic basis functions associated with nodes in element 1.

A common terminology is to speak about linear elements as elements with two local nodes associated with piecewise linear basis functions. Similarly, quadratic elements and cubic elements refer to piecewise quadratic or cubic functions over elements with three or four local nodes, respectively. Alternative names, frequently used later, are P1 elements for linear elements, P2 for quadratic elements, and so forth: Pd signifies degree \(d\) of the polynomial basis functions.

Calculating the linear system¶

The elements in the coefficient matrix and right-hand side are given by the formulas (3.4) and (3.5), but now the choice of \({\psi}_i\) is \({\varphi}_i\). Consider P1 elements where \({\varphi}_i(x)\) piecewise linear. Nodes and elements numbered consecutively from left to right in a uniformly partitioned mesh imply the nodes

and the elements

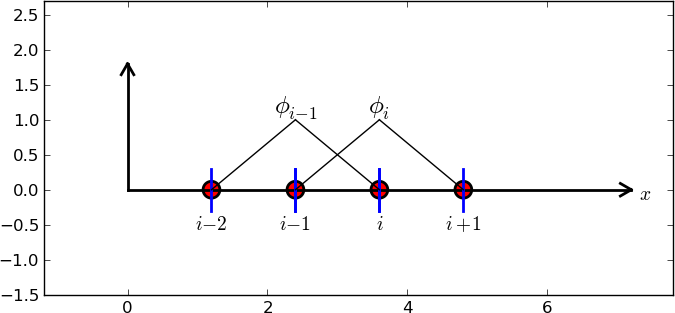

We have in this case \(N\) elements and \(N+1\) nodes, and \(\Omega=[x_{0},x_{N}]\). The formula for \({\varphi}_i(x)\) is given by (3) and a graphical illustration is provided in Figures Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions associated with nodes in element 1 and Illustration of two neighboring linear (hat) functions with general node numbers. First we clearly see from the figures the very important property \({\varphi}_i(x){\varphi}_j(x)\neq 0\) if and only if \(j=i-1\), \(j=i\), or \(j=i+1\), or alternatively expressed, if and only if \(i\) and \(j\) are nodes in the same element. Otherwise, \({\varphi}_i\) and \({\varphi}_j\) are too distant to have an overlap and consequently their product vanishes.

Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions corresponding to global node 2 and 3

Calculating a specific matrix entry¶

Let us calculate the specific matrix entry \(A_{2,3} = \int_\Omega {\varphi}_2{\varphi}_3{\, \mathrm{d}x}\). Figure Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions corresponding to global node 2 and 3 shows how \({\varphi}_2\) and \({\varphi}_3\) look like. We realize from this figure that the product \({\varphi}_2{\varphi}_3\neq 0\) only over element 2, which contains node 2 and 3. The particular formulas for \({\varphi}_{2}(x)\) and \({\varphi}_3(x)\) on \([x_{2},x_{3}]\) are found from (3). The function \({\varphi}_3\) has positive slope over \([x_{2},x_{3}]\) and corresponds to the interval \([x_{i-1},x_{i}]\) in (3). With \(i=3\) we get

while \({\varphi}_2(x)\) has negative slope over \([x_{2},x_{3}]\) and corresponds to setting \(i=2\) in (3),

We can now easily integrate,

The diagonal entry in the coefficient matrix becomes

The entry \(A_{2,1}\) has an the integral that is geometrically similar to the situation in Figure Illustration of the piecewise linear basis functions corresponding to global node 2 and 3, so we get \(A_{2,1}=h/6\).

Calculating a general row in the matrix¶

We can now generalize the calculation of matrix entries to a general row number \(i\). The entry \(A_{i,i-1}=\int_\Omega{\varphi}_i{\varphi}_{i-1}{\, \mathrm{d}x}\) involves hat functions as depicted in Figure Illustration of two neighboring linear (hat) functions with general node numbers. Since the integral is geometrically identical to the situation with specific nodes 2 and 3, we realize that \(A_{i,i-1}=A_{i,i+1}=h/6\) and \(A_{i,i}=2h/3\). However, we can compute the integral directly too:

The particular formulas for \({\varphi}_{i-1}(x)\) and \({\varphi}_i(x)\) on \([x_{i-1},x_{i}]\) are found from (3): \({\varphi}_i\) is the linear function with positive slope, corresponding to the interval \([x_{i-1},x_{i}]\) in (3), while \(\phi_{i-1}\) has a negative slope so the definition in interval \([x_{i},x_{i+1}]\) in (3) must be used. (The appearance of \(i\) in (3) and the integral might be confusing, as we speak about two different \(i\) indices.)

Illustration of two neighboring linear (hat) functions with general node numbers

The first and last row of the coefficient matrix lead to slightly different integrals:

Similarly, \(A_{N,N}\) involves an integral over only one element and equals hence \(h/3\).

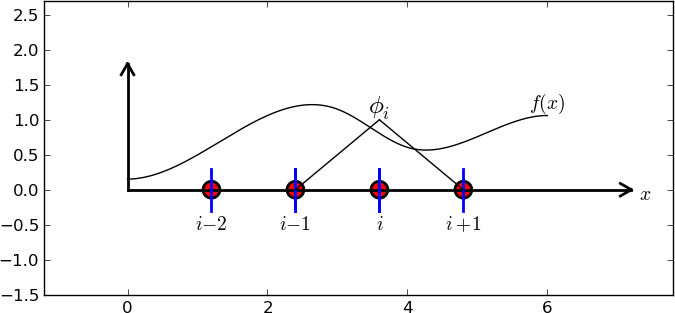

Right-hand side integral with the product of a basis function and the given function to approximate

The general formula for \(b_i\), see Figure Right-hand side integral with the product of a basis function and the given function to approximate, is now easy to set up

We need a specific \(f(x)\) function to compute these integrals. With two equal-sized elements in \(\Omega=[0,1]\) and \(f(x)=x(1-x)\), one gets

The solution becomes

The resulting function

is displayed in Figure Least squares approximation of a parabola using 2 (left) and 4 (right) P1 elements (left). Doubling the number of elements to four leads to the improved approximation in the right part of Figure Least squares approximation of a parabola using 2 (left) and 4 (right) P1 elements.

Least squares approximation of a parabola using 2 (left) and 4 (right) P1 elements

Assembly of elementwise computations¶

The integrals above are naturally split into integrals over individual elements since the formulas change with the elements. This idea of splitting the integral is fundamental in all practical implementations of the finite element method.

Let us split the integral over \(\Omega\) into a sum of contributions from each element:

Now, \(A^{(e)}_{i,j}\neq 0\) if and only if \(i\) and \(j\) are nodes in element \(e\). Introduce \(i=q(e,r)\) as the mapping of local node number \(r\) in element \(e\) to the global node number \(i\). This is just a short mathematical notation for the expression i=elements[e][r] in a program. Let \(r\) and \(s\) be the local node numbers corresponding to the global node numbers \(i=q(e,r)\) and \(j=q(e,s)\). With \(d\) nodes per element, all the nonzero elements in \(A^{(e)}_{i,j}\) arise from the integrals involving basis functions with indices corresponding to the global node numbers in element number \(e\):

These contributions can be collected in a \((d+1)\times (d+1)\) matrix known as the element matrix. Let \({I_d}=\{0,\ldots,d\}\) be the valid indices of \(r\) and \(s\). We introduce the notation

for the element matrix. For the case \(d=2\) we have

Given the numbers \(\tilde A^{(e)}_{r,s}\), we should according to (5) add the contributions to the global coefficient matrix by

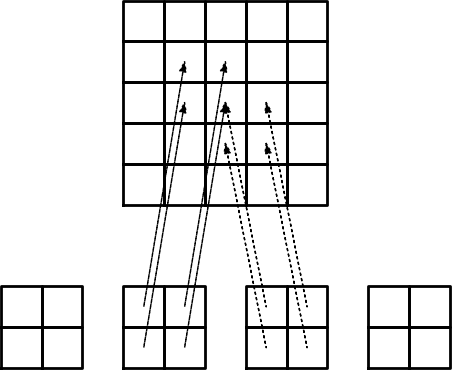

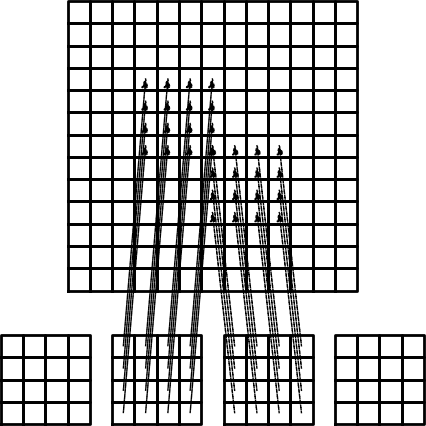

This process of adding in elementwise contributions to the global matrix is called finite element assembly or simply assembly. Figure Illustration of matrix assembly: regularly numbered P1 elements illustrates how element matrices for elements with two nodes are added into the global matrix. More specifically, the figure shows how the element matrix associated with elements 1 and 2 assembled, assuming that global nodes are numbered from left to right in the domain. With regularly numbered P3 elements, where the element matrices have size \(4\times 4\), the assembly of elements 1 and 2 are sketched in Figure Illustration of matrix assembly: regularly numbered P3 elements.

Illustration of matrix assembly: regularly numbered P1 elements

Illustration of matrix assembly: regularly numbered P3 elements

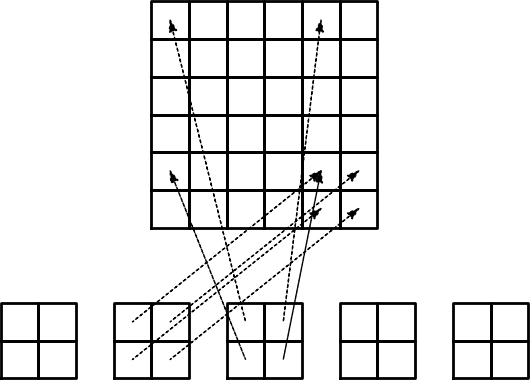

After assembly of element matrices corresponding to regularly numbered elements and nodes are understood, it is wise to study the assembly process for irregularly numbered elements and nodes. Figure Example on irregular numbering of elements and nodes shows a mesh where the elements array, or \(q(e,r)\) mapping in mathematical notation, is given as

elements = [[2, 1], [4, 5], [0, 4], [3, 0], [5, 2]]

The associated assembly of element matrices 1 and 2 is sketched in Figure Illustration of matrix assembly: irregularly numbered P1 elements.

These three assembly processes can also be animated.

Illustration of matrix assembly: irregularly numbered P1 elements

The right-hand side of the linear system is also computed elementwise:

We observe that \(b_i^{(e)}\neq 0\) if and only if global node \(i\) is a node in element \(e\). With \(d\) nodes per element we can collect the \(d+1\) nonzero contributions \(b_i^{(e)}\), for \(i=q(e,r)\), \(r\in{I_d}\), in an element vector

These contributions are added to the global right-hand side by an assembly process similar to that for the element matrices:

Mapping to a reference element¶

Instead of computing the integrals

over some element \(\Omega^{(e)} = [x_L, x_R]\), it is convenient to map the element domain \([x_L, x_R]\) to a standardized reference element domain \([-1,1]\). (We have now introduced \(x_L\) and \(x_R\) as the left and right boundary points of an arbitrary element. With a natural, regular numbering of nodes and elements from left to right through the domain, we have \(x_L=x_{e}\) and \(x_R=x_{e+1}\) for P1 elements.)

Let \(X\in [-1,1]\) be the coordinate in the reference element. A linear or affine mapping from \(X\) to \(x\) reads

This relation can alternatively be expressed by

where we have introduced the element midpoint \(x_m=(x_L+x_R)/2\) and the element length \(h=x_R-x_L\).

Integrating on the reference element is a matter of just changing the integration variable from \(x\) to \(X\). Let

be the basis function associated with local node number \(r\) in the reference element. The integral transformation reads

The stretch factor \(dx/dX\) between the \(x\) and \(X\) coordinates becomes the determinant of the Jacobian matrix of the mapping between the coordinate systems in 2D and 3D. To obtain a uniform notation for 1D, 2D, and 3D problems we therefore replace \(dx/dX\) by \(\det J\) already now. In 1D, \(\det J = dx/dX = h/2\). The integration over the reference element is then written as

The corresponding formula for the element vector entries becomes

Since we from now on will work in the reference element, we need explicit mathematical formulas for the basis functions \({\varphi}_i(x)\) in the reference element only, i.e., we only need to specify formulas for \({\tilde{\varphi}}_r(X)\). This is a very convenient simplification compared to specifying piecewise polynomials in the physical domain.

The \({\tilde{\varphi}}_r(x)\) functions are simply the Lagrange polynomials defined through the local nodes in the reference element. For \(d=1\) and two nodes per element, we have the linear Lagrange polynomials

Quadratic polynomials, \(d=2\), have the formulas

In general,

where \(X_{(0)},\ldots,X_{(d)}\) are the coordinates of the local nodes in the reference element. These are normally uniformly spaced: \(X_{(r)} = -1 + 2r/d\), \(r\in{I_d}\).

Why reference elements

The great advantage of using reference elements is that the formulas for the basis functions, \({\tilde{\varphi}}_r(X)\), are the same for all elements and independent of the element geometry (length and location in the mesh). The geometric information is “factored out” in the simple mapping formula and the associated \(\det J\) quantity, but this information is (here taken as) the same for element types. Also, the integration domain is the same for all elements.

Example: Integration over a reference element¶

To illustrate the concepts from the previous section in a specific example, we now consider calculation of the element matrix and vector for a specific choice of \(d\) and \(f(x)\). A simple choice is \(d=1\) (P1 elements) and \(f(x)=x(1-x)\) on \(\Omega =[0,1]\). We have the general expressions (8) and (9) for \(\tilde A^{(e)}_{r,s}\) and \(\tilde b^{(e)}_{r}\). Writing these out for the choices (10) and (11), and using that \(\det J = h/2\), we can do the following calculations of the element matrix entries:

The corresponding entries in the element vector becomes

In the last two expressions we have used the element midpoint \(x_m\).

Integration of lower-degree polynomials above is tedious, and higher-degree polynomials involve very much more algebra, but sympy may help. For example, we can easily calculate (12), (12), and (15) by

>>> import sympy as sp

>>> x, x_m, h, X = sp.symbols('x x_m h X')

>>> sp.integrate(h/8*(1-X)**2, (X, -1, 1))

h/3

>>> sp.integrate(h/8*(1+X)*(1-X), (X, -1, 1))

h/6

>>> x = x_m + h/2*X

>>> b_0 = sp.integrate(h/4*x*(1-x)*(1-X), (X, -1, 1))

>>> print b_0

-h**3/24 + h**2*x_m/6 - h**2/12 - h*x_m**2/2 + h*x_m/2

For inclusion of formulas in documents (like the present one), sympy can print expressions in LaTeX format:

>>> print sp.latex(b_0, mode='plain')

- \frac{1}{24} h^{3} + \frac{1}{6} h^{2} x_{m}

- \frac{1}{12} h^{2} - \half h x_{m}^{2}

+ \half h x_{m}