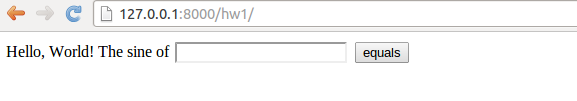

Figure 4: The input page.

The Django application is about filling the files views.py and models.py

with content. The mathematical computations are performed in compute.py

so we copy this file from the mvc directory to the hw1 directory

for convenience (we could alternatively add ../mvc to sys.path such that

import compute would work from the hw1 directory).

The web application offers a text field where the user can

write the value of r, see Figure 4.

After clicking on the equals button,

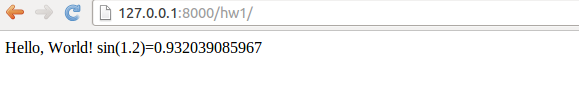

the mathematics is performed and a new page as

seen in Figure 5 appears.

Figure 4: The input page.

Figure 5: The result page.

The models.py file contains the model, which consists

of the data we need in the application, stored in Django's data types.

Our data consists of one number, called r, and models.py then

look like

from django.db import models

from django.forms import ModelForm

class Input(models.Model):

r = models.FloatField()

class InputForm(ModelForm):

class Meta:

model = Input

Input class lists variables representing data as static class

attributes. The django.db.models module contains various classes

for different types of data, here we use FloatField to represent

a floating-point number.

The InputForm class has a the shown generic form across applications

if we by convention apply the name Input for the class holding the data.

The views.py file contains a function index which defines

the actions we want to perform when invoking

the URL ( here http://127.0.0.1:8000/hw1/).

In addition, views.py has the present_output function from

the view.py file in the mvc directory.

from django.shortcuts import render_to_response

from django.template import RequestContext

from django.http import HttpResponse

from models import InputForm

from compute import compute

def index(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

form = InputForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

form = form.save(commit=False)

return present_output(form)

else:

form = InputForm()

return render_to_response('hw1.html',

{'form': form}, context_instance=RequestContext(request))

def present_output(form):

r = form.r

s = compute(r)

return HttpResponse('Hello, World! sin(%s)=%s' % (r, s))

The index function deserves some explanation. It must take one

argument, usually called request. There are two modes in the function. Either

the user has provided input on the web page, which means that

request.method equals 'POST', or we show a new web page

with which the user is supposed to interact.

The input consists of a web form with

one field where we can fill in our r variable. This page

is realized by the two central statements

# Make info needed in the web form

form = InputForm()

# Make HTML code

render_to_response('hw1.html',

{'form': form}, context_instance=RequestContext(request))

hw1.html file resides in the templates subdirectory and contains

a template for the HTML code:

<form method="post" action="">{% csrf_token %}

Hello, World! The sine of {{ form.r }}

<input type="submit" value="equals" />

</form>

{% csrf_token %} and variables like {{ form.r }}. Django will

replace the former by some appropriate HTML statements, while the

latter simply extracts the numerical value of the variable r in

our form (specified in the Input class in models.py).

Typically, this hw1.html file

results in the HTML code

<form method="post" action="">

<div style='display:none'>

<input type='hidden' name='csrfmiddlewaretoken'

value='oPWMuuy1gLlXm9GvUZINv49eVUYnux5Q' /></div>

Hello, World! The sine of <input type="text" name="r" id="id_r" />

<input type="submit" value="equals" />

</form>

When then user has filled in a value in the text field on the input

page, the index function is called again and request.method equals

'POST'. A new form object is made, this time with user info (request.POST).

We can check that the form is valid and if so, proceed with

computations followed by presenting the results in a

new web page (see Figure 5):

def index(request):

if request.method == 'POST':

form = InputForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

form = form.save(commit=False)

return present_output(form)

def present_output(form):

r = form.r

s = compute(r)

return HttpResponse('Hello, World! sin(%s)=%s' % (r, s))

r as given by the user is available as form.r.

Instead of using a template for the output page, which is natural to

do in more advanced cases, we here illustrate the possibility to

send raw HTML to the output page by returning an HttpResponse

object initialized by a string containing the desired HTML code.

Launch this application by filling in the address http://127.0.0.1:8000/hw1/

in your web browser. Make sure the Django development server is running,

and if not, restart it by

Terminal> python ../../../django_project/manage.py runserver

views.py

file in an editor and add some color to the output HTML code from

the present_output function:

return HttpResponse("""

<font color='blue'>Hello</font>, World!

sin(%s)=%s

"""% (r, s))

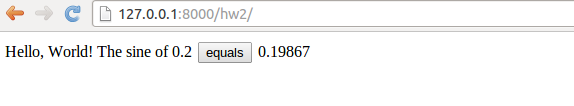

Instead of making a separate output page with the result, we can simply add the sine value to the input page. This makes the user feel that she interacts with the same page, as when operating a calculator. The output page should then look as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: The modified result page.

We need to make a new Django application, now called

hw2.

Instead of running the standard

manage.py startapp hw2 command,

we can simply copy the hw1

directory to hw2. We need, of course, to add information about this

new application in settings.py and urls.py.

In the former file we must have

TEMPLATE_DIRS = (

relative2absolute_path('../../apps/django_apps/hw1/templates'),

relative2absolute_path('../../apps/django_apps/hw2/templates'),

)

INSTALLED_APPS = (

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.sites',

'django.contrib.messages',

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

# Uncomment the next line to enable the admin:

# 'django.contrib.admin',

# Uncomment the next line to enable admin documentation:

# 'django.contrib.admindocs',

'hw1',

'hw2',

)

urls.py we add the URL hw2 which is to call our index function

in the views.py file of the hw2 app:

urlpatterns = patterns('',

url(r'^hw1/', 'django_apps.hw1.views.index'),

url(r'^hw2/', 'django_apps.hw2.views.index'),

The views.py file changes a bit since we shall generate almost the same

web page on input and output. This makes the present_output function

unnatural, and everything is done within the index function:

def index(request):

s = None # initial value of result

if request.method == 'POST':

form = InputForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

form = form.save(commit=False)

r = form.r

s = compute(r)

else:

form = InputForm()

return render_to_response('hw2.html',

{'form': form,

's': '%.5f' % s if isinstance(s, float) else ''

}, context_instance=RequestContext(request))

Note that the output variable s is computed within the index

function and defaults to None. The template file hw2.html

looks like

<form method="post" action="">{% csrf_token %}

Hello, World! The sine of {{ form.r }}

<input type="submit" value="equals" />

{% if s != '' %}

{{ s }}

{% endif %}

</form>

hw1.html is that we right after the equals

button write out the value of s. However, we make a test that

the value is only written if it is computed, here recognized by

being a non-empty string. The s in the template file

is substituted by the value of the object

corresponding to the key 's' in the

dictionary we pass to the render_to_response. As seen,

we pass a string where s is formatted with five digits if s

is a float, i.e., if s is computed. Otherwise, s has the

default value None and we send an empty string to the template.

The template language allows tests using Python syntax, but the

if-block must be explicitly ended by {% endif %}.