A generalized element concept¶

So far, finite element computing has employed the nodes and

element lists together with the definition of the basis functions

in the reference element. Suppose we want to introduce a piecewise

constant approximation with one basis function \({\tilde{\varphi}}_0(x)=1\) in

the reference element, corresponding to a \({\varphi}_i(x)\) function that

is 1 on element number \(i\) and zero on all other elements.

Although we could associate the function value

with a node in the middle of the elements, there are no nodes at the

ends, and the previous code snippets will not work because we

cannot find the element boundaries from the nodes list.

In order to get a richer space of finite element approximations, we need to revise the simple node and element concept presented so far and introduce a more powerful terminology. Much literature employs the definition of node and element introduced in the previous sections so it is important have this knowledge, besides being a good pedagogical background from understanding the extended element concept in the following.

Cells, vertices, and degrees of freedom¶

We now introduce cells as the subdomains \(\Omega^{(e)}\) previously referred to as elements. The cell boundaries are denoted as vertices. The reason for this name is that cells are recognized by their vertices in 2D and 3D. We also define a set of degrees of freedom (dof), which are the quantities we aim to compute. The most common type of degree of freedom is the value of the unknown function \(u\) at some point. (For example, we can introduce nodes as before and say the degrees of freedom are the values of \(u\) at the nodes.) The basis functions are constructed so that they equal unity for one particular degree of freedom and zero for the rest. This property ensures that when we evaluate \(u=\sum_j c_j{\varphi}_j\) for degree of freedom number \(i\), we get \(u=c_i\). Integrals are performed over cells, usually by mapping the cell of interest to a reference cell.

With the concepts of cells, vertices, and degrees of freedom we increase the decoupling of the geometry (cell, vertices) from the space of basis functions. We will associate different sets of basis functions with a cell. In 1D, all cells are intervals, while in 2D we can have cells that are triangles with straight sides, or any polygon, or in fact any two-dimensional geometry. Triangles and quadrilaterals are most common, though. The popular cell types in 3D are tetrahedra and hexahedra.

Extended finite element concept¶

The concept of a finite element is now

- a reference cell in a local reference coordinate system;

- a set of basis functions \({\tilde{\varphi}}_i\) defined on the cell;

- a set of degrees of freedom that uniquely determines the basis functions such that \({\tilde{\varphi}}_i=1\) for degree of freedom number \(i\) and \({\tilde{\varphi}}_i=0\) for all other degrees of freedom;

- a mapping between local and global degree of freedom numbers, here called the dof map;

- a geometric mapping of the reference cell onto the cell in the physical domain.

There must be a geometric description of a cell. This is trivial in 1D since the cell is an interval and is described by the interval limits, here called vertices. If the cell is \(\Omega^{(e)}=[x_L,x_R]\), vertex 0 is \(x_L\) and vertex 1 is \(x_R\). The reference cell in 1D is \([-1,1]\) in the reference coordinate system \(X\).

The expansion of \(u\) over one cell is often used:

where the sum is taken over the numbers of the degrees of freedom and \(c_r\) is the value of \(u\) for degree of freedom number \(r\).

Our previous P1, P2, etc., elements are defined by introducing \(d+1\)

equally spaced nodes in the reference cell and saying that the degrees

of freedom are the \(d+1\) function values at these nodes. The basis

functions must be 1 at one node and 0 at the others, and the Lagrange

polynomials have exactly this property. The nodes can be numbered

from left to right with associated degrees of freedom that are

numbered in the same way. The degree of freedom mapping becomes what

was previously represented by the elements lists. The cell mapping

is the same affine mapping (70) as

before.

Implementation¶

Implementationwise,

- we replace

nodesbyvertices;- we introduce

cellssuch thatcell[e][r]gives the mapping from local vertexrin celleto the global vertex number invertices;- we replace

elementsbydof_map(the contents are the same for Pd elements).

Consider the example from the section Elements and nodes where \(\Omega =[0,1]\) is divided into two cells, \(\Omega^{(0)}=[0,0.4]\) and \(\Omega^{(1)}=[0.4,1]\), as depicted in Figure Finite element mesh with 2 elements and 5 nodes. The vertices are \([0,0.4,1]\). Local vertex 0 and 1 are \(0\) and \(0.4\) in cell 0 and \(0.4\) and \(1\) in cell 1. A P2 element means that the degrees of freedom are the value of \(u\) at three equally spaced points (nodes) in each cell. The data structures become

vertices = [0, 0.4, 1]

cells = [[0, 1], [1, 2]]

dof_map = [[0, 1, 2], [2, 3, 4]]

If we would approximate \(f\) by piecewise constants, known as

P0 elements, we simply

introduce one point or node in an element, preferably \(X=0\),

and define one degree of freedom, which is the function value

at this node. Moreover, we set \({\tilde{\varphi}}_0(X)=1\).

The cells and vertices arrays remain the same, but

dof_map is altered:

dof_map = [[0], [1]]

We use the cells and vertices lists to retrieve information

on the geometry of a cell, while dof_map is the

\(q(e,r)\) mapping introduced earlier in the

assembly of element matrices and vectors.

For example, the Omega_e variable (representing the cell interval)

in previous code snippets must now be computed as

Omega_e = [vertices[cells[e][0], vertices[cells[e][1]]

The assembly is done by

A[dof_map[e][r], dof_map[e][s]] += A_e[r,s]

b[dof_map[e][r]] += b_e[r]

We will hereafter drop the nodes and elements arrays

and work exclusively with cells, vertices, and dof_map.

The module fe_approx1D_numint.py now replaces the module

fe_approx1D and offers similar functions that work with

the new concepts:

from fe_approx1D_numint import *

x = sym.Symbol('x')

f = x*(1 - x)

N_e = 10

vertices, cells, dof_map = mesh_uniform(N_e, d=3, Omega=[0,1])

phi = [basis(len(dof_map[e])-1) for e in range(N_e)]

A, b = assemble(vertices, cells, dof_map, phi, f)

c = np.linalg.solve(A, b)

# Make very fine mesh and sample u(x) on this mesh for plotting

x_u, u = u_glob(c, vertices, cells, dof_map,

resolution_per_element=51)

plot(x_u, u)

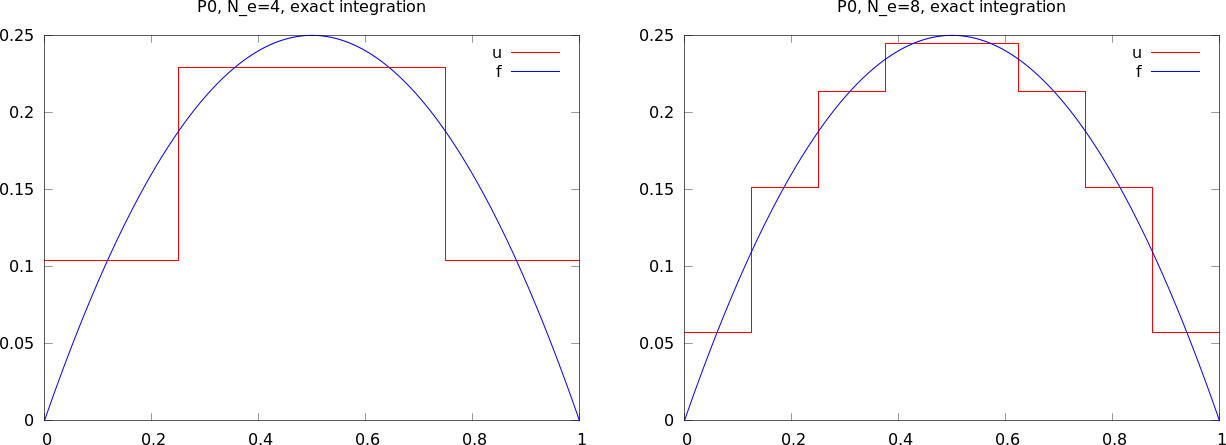

These steps are offered in the approximate function, which we here

apply to see how well four P0 elements (piecewise constants)

can approximate a parabola:

from fe_approx1D_numint import *

x=sym.Symbol("x")

for N_e in 4, 8:

approximate(x*(1-x), d=0, N_e=N_e, Omega=[0,1])

Figure Approximation of a parabola by 4 (left) and 8 (right) P0 elements shows the result.

Computing the error of the approximation¶

So far we have focused on computing the coefficients \(c_j\) in the approximation \(u(x)=\sum_jc_j{\varphi}_j\) as well as on plotting \(u\) and \(f\) for visual comparison. A more quantitative comparison needs to investigate the error \(e(x)=f(x)-u(x)\). We mostly want a single number to reflect the error and use a norm for this purpose, usually the \(L^2\) norm

Since the finite element approximation is defined for all \(x\in\Omega\),

and we are interested in how \(u(x)\) deviates from \(f(x)\) through all

the elements,

we can either integrate analytically or use an accurate numerical

approximation. The latter is more convenient as it is a generally

feasible and simple approach. The idea is to sample \(e(x)\)

at a large number of points in each element. The function u_glob

in the fe_approx1D_numint module does this for \(u(x)\) and returns

an array x with coordinates and an array u with the \(u\) values:

x, u = u_glob(c, vertices, cells, dof_map,

resolution_per_element=101)

e = f(x) - u

Let us use the Trapezoidal method to approximate the integral. Because

different elements may have different lengths, the x array has

a non-uniformly distributed set of coordinates. Also, the u_glob

function works in an element by element fashion such that coordinates

at the boundaries between elements appear twice. We therefore need

to use a “raw” version of the Trapezoidal rule where we just add up

all the trapezoids:

if \(x_0,\ldots,x_n\) are all the coordinates in x. In

vectorized Python code,

g_x = g(x)

integral = 0.5*np.sum((g_x[:-1] + g_x[1:])*(x[1:] - x[:-1]))

Computing the \(L^2\) norm of the error, here named E, is now achieved by

e2 = e**2

E = np.sqrt(0.5*np.sum((e2[:-1] + e2[1:])*(x[1:] - x[:-1]))

How does the error depend on \(h\) and \(d\)

Theory and experiments show that the least squares or projection/Galerkin method in combination with Pd elements of equal length \(h\) has an error

Example: Cubic Hermite polynomials¶

The finite elements considered so far represent \(u\) as piecewise polynomials with discontinuous derivatives at the cell boundaries. Sometimes it is desirable to have continuous derivatives. A primary example is the solution of differential equations with fourth-order derivatives where standard finite element formulations lead to a need for basis functions with continuous first-order derivatives. The most common type of such basis functions in 1D is the so-called cubic Hermite polynomials. The construction of such polynomials, as explained next, will further exemplify the concepts of a cell, vertex, degree of freedom, and dof map.

Given a reference cell \([-1,1]\), we seek cubic polynomials with the values of the function and its first-order derivative at \(X=-1\) and \(X=1\) as the four degrees of freedom. Let us number the degrees of freedom as

- 0: value of function at \(X=-1\)

- 1: value of first derivative at \(X=-1\)

- 2: value of function at \(X=1\)

- 3: value of first derivative at \(X=1\)

By having the derivatives as unknowns, we ensure that the derivative of a basis function in two neighboring elements is the same at the node points.

The four basis functions can be written in a general form

with four coefficients \(C_{i,j}\), \(j=0,1,2,3\), to be determined for each \(i\). The constraints that basis function number \(i\) must be 1 for degree of freedom number \(i\) and zero for the other three degrees of freedom, gives four equations to determine \(C_{i,j}\) for each \(i\). In mathematical detail,

These four \(4\times 4\) linear equations can be solved, yielding the following formulas for the cubic basis functions:

global degrees of freedom. A natural left-to-right numbering has the function value at vertex \(x_{i}\) as degree of freedom number \(2i\) and the value of the derivative at \(x_{i}\) as degree of freedom number \(2i+1\), \(i=0,\ldots,N_e+1\).