Making a Flask application

Not much code or configuration is needed to make a Flask application. Actually one short file is enough. For this file to work you need to install Flask and some corresponding packages. This is easiest performed by

Terminal> sudo pip install --upgrade Flask

Terminal> sudo pip install --upgrade Flask-WTF

The --upgrade option ensures that you upgrade to the latest version in

case you already have these packages.

Programming the Flask application

The user interaction

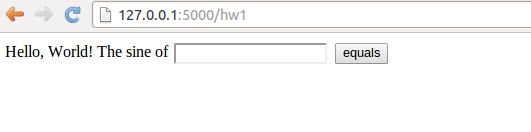

We want our input page to feature a text field where the user can

write the value of r, see Figure 1.

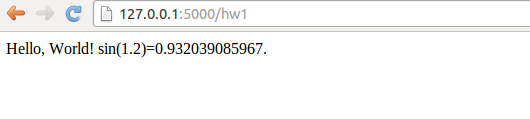

By clicking on the equals button

the corresponding s value is computed and written out the result page

seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1: The input page.

Figure 2: The output page.

The Python code

Flask does not require us to use the MVC pattern so there is actually

no need to split the original program into model, view, controller,

and compute files as already explained (but it will be

done later). First we make a controller.py file where the view, the

model, and the controller parts appear within the same file.

The compute component is always in a separate file as

we like to encapsulate the computations completely from user

interfaces.

The view that the user sees is determined by

HTML templates in a subdirectory templates, and consequently

we name the template files view*.html.

The model and other parts of the view concept are just parts of

the controller.py file. The complete file is short and explained

in detail below.

from flask import Flask, render_template, request

from wtforms import Form, FloatField, validators

from compute import compute

app = Flask(__name__)

# Model

class InputForm(Form):

r = FloatField(validators=[validators.InputRequired()])

# View

@app.route('/hw1', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def index():

form = InputForm(request.form)

if request.method == 'POST' and form.validate():

r = form.r.data

s = compute(r)

return render_template("view_output.html", form=form, s=s)

else:

return render_template("view_input.html", form=form)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

Dissection

The web application is the app object of class Flask, and

initialized as shown. The model is a special Flask class derived from

Form where the input variable in the app is listed as a static class

attribute and initialized by a special form field object from the

wtforms package. Such form field objects correspond to HTML forms

in the input page. For the r variable we apply FloatField since

it is a floating-point variable. A default validator, here checking

that the user supplies a real number, is automatically included, but

we add another validator, InputRequired, to force the user to

provide input before clicking on the equals button.

The view part of this Python code consists of a URL and a

corresponding function to call when the URL is invoked. The function

name is here chosen to be index (inspired by the standard

index.html page that is the main page of a web app). The decorator

@app.route('/hw1', ...) maps the URL http://127.0.0.1:5000/hw1 to

a call to index. The methods argument must be as shown to allow

the user to communicate with the web page.

The index function first makes a form object based on the data in

the model, here class InputForm. Then there are two possibilities:

either the user has provided data in the HTML form or the user is

to be offered an input form. In the former case, request.method

equals 'POST' and we can extract the numerical value of r

from the form object, using form.r.data, call up our mathematical

computations, and make a web page with the result.

In the latter case, we make an input page as displayed in

Figure 1.

The template files

Making a web page with Flask is conveniently done by an HTML

template. Since the output page is simplest we display the

view_output.html template first:

Hello, World! sin({{ form.r.data }})={{s}}.

Keyword arguments sent to render_template are available in the

HTML template. Here we have the keyword arguments form and s.

With the form object we extract the value of

r in the HTML code by {{ form.r.data }}. Similarly, the value of s

is simply {{ s }}.

The HTML template for the input page is slightly more complicated as we need to use an HTML form:

<form method=post action="">

Hello, World! The sine of {{ form.r }}

<input type=submit value=equals>

</form>

Testing the application

We collect the files associated with a Flask application (often called just app) in a directory, here called hw1. All you have to do in order to run this web application is to find this directory and run

Terminal> python controller.py

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000/

* Restarting with reloader

Open a new window or tab in your browser and type in the URL

http://127.0.0.1:5000/hw1.

Equipping the input page with output results

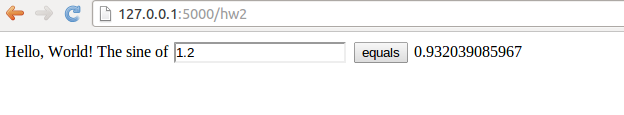

Our application made two distinct pages for grabbing input from the user and presenting the result. It is often more natural to add the result to the input page. This is particularly the case in the present web application, which is a kind of calculator. Figure 3 shows what the user sees after clicking the equals button.

Figure 3: The modified result page.

To let the user stay within the same page, we create a new directory

hw2

for this modified Flask app and copy the files from the previous

hw1 directory. The idea now is to make use of just one

template, in templates/view.html:

<form method=post action="">

Hello, World! The sine of

{{( form.r )}}

<input type=submit value=equals>

{% if s != None %}

{{s}}

{% endif %}

</form>

The form is identical to what we used in view_input.html in

the hw1 directory, and the only

new thing is the output of s below the form.

The template language supports some programming with Python objects

inside {% and %} tags.

Specifically in this file, we can test on the value of s:

if it is None, we know that the computations are not performed and

s should not appear on the page, otherwise s holds the sine

value and we can write it out. Note that, contrary to plain Python,

the template language does not rely on indentation of blocks and

therefore needs an explicit end statement {% endif %} to finish

the if-test.

The generated HTML code from this template file reads

<form method=post action="">

Hello, World! The sine of

<input id="r" name="r" type="text" value="1.2">

<input type=submit value=equals>

0.932039085967

</form>

The index function of our modified application

needs adjustments since we use the same

template for the input and the output page:

# View

@app.route('/hw2', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def index():

form = InputForm(request.form)

if request.method == 'POST' and form.validate():

r = form.r.data

s = compute(r)

else:

s = None

return render_template("view.html", form=form, s=s)

It is seen that if the user has given data, s is a float, otherwise

s is None. You are encouraged to test the app by running

Terminal> python controller.py

and loading http://127.0.0.1:5000/hw2 into your browser.

A nice little exercise is to control the formatting of the result s.

To this end, you can simply transform s to a string: s = '%.5f' % s before

sending it to render_template.

Splitting the app into model, view, and controller files

In our previous two Flask apps we have had the view displayed for the

user in a separate template file, and the computations as always in

compute.py, but everything else was placed in one file controller.py.

For illustration of the MVC concept we

may split the controller.py into two files: model.py and

controller.py. The view is in templates/view.html.

These new files are located in a

directory

hw3_flask

The contents

in the files reflect the splitting introduced in the original

scientific hello world program in the section Application of the MVC pattern.

The model.py file now consists of the input form class:

from wtforms import Form, FloatField, validators

class InputForm(Form):

r = FloatField(validators=[validators.InputRequired()])

The file templates/view.html is as before, while controller.py contains

from flask import Flask, render_template, request

from compute import compute

from model import InputForm

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/hw3', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def index():

form = InputForm(request.form)

if request.method == 'POST' and form.validate():

r = form.r.data

s = compute(r)

else:

s = None

return render_template("view.html", form=form, s=s)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

The statements are indentical to those in the hw2 app, only

the organization of the statement in files differ.