A Tutorial for the Odespy Interface to ODE Solvers¶

| Authors: | Hans Petter Langtangen, Liwei Wang |

|---|---|

| Date: | May 1, 2015 |

The Odespy package makes it easy to specify an ODE problem in Python and get it solved by a wide variety of different numerical methods and software.

Motivation¶

The Odespy package grew out of the desire to have a unified interface to lots of different methods and software for ODEs. Consider the ODE problem

known as the van der Pool oscillator. The solution is desired at 150 equally spaced time levels in the interval [0, 30].

Traditional Approach¶

We want to solve this problem by three well-known routines:

- LSODE from ODEPACK (adaptive Adams and BDF methods)

- ode45 from MATLAB (adaptive Runge-Kutta 4-5-th order)

- vode from Python (adaptive Adams and BDF methods)

All of these routines require the ODE problem to be on the form \(u'=f(u,t)\), which means that the second-order differential equation must be recast as a system of two ODEs,

and we have to identify the two components of the \(f(u,t)\) function:

The corresponding boundary conditions become

The mentioned ODE software needs a specification of the \(f(u,t)\) formulas through some user-written function that takes \(u\) and \(t\) as input and delivers the vector \(f\) as output.

LSODE¶

Application of LSODE and other ODEPACK routines requires the ODE problem to be specified in FORTRAN and the solver to be called from FORTRAN:

PROGRAM MAIN

EXTERNAL F

INTEGER I, IOPT, IOUT, ISTATE, ITASK, ITOL, IWORK,

1 LRW, LIW, MF, NEQ, NOUT

DOUBLE PRECISION ATOL, T, TOUT, RTOL, RWORK, U, URR

DIMENSION U(2), RWORK(52), IWORK(20), U1(5), U2(5)

NEQ = 2

C SET ADAMS METHOD:

MF = 10

C LET TOLERANCES BE SCALARS (NOT ARRAYS):

ITOL = 1

C USE ONLY ABSOLUTE TOLERANCE:

RTOL = 0.0D0

ATOL = 1.0D-6

LRW = 52

LIW = 20

C NUMBER OF TIME STEPS:

NOUT = 150

C FINAL TIME:

TOUT = 30.0D0

C INITIAL CONDITIONS

T = 0.0D0

U(1)= 2.0D0

U(2) = 0.0D0

ITASK = 1

ISTATE = 1

C CALL ADAPTIVE TIME STEPPING AT EACH OF THE TARGET TIME LEVELS

DO 100 IOUT = 1, NOUT

CALL DLSODE(F,NEQ,U,T,TOUT,ITOL,RTOL,ATOL,ITASK,

1 ISTATE,IOPT,RWORK,LRW,IWORK,LIW,JAC,MF)

U1(IOUT) = U(1)

U2(IOUT) = U(2)

TOUT = TOUT + 2.0D-1

100 CONTINUE

END

SUBROUTINE F(NEQ, T, U, UDOT)

INTEGER NEQ

DOUBLE PRECISION T, U, UDOT

DIMENSION U(2), UDOT(2)

UDOT(1) = U(2)

UDOT(2) = 3.0D0*(1.0D0 - U(1)*U(1))*U(2) - U(1)

RETURN

END

MATLAB¶

The problem can be solved with very compact code in MATLAB. The definition of the ODE system, the \(f(u,t)\) function, is placed in a function in a file, say myode.m:

function F = myode(t, u);

F(1,1) = u(2)

F(2,1) = 3*(1 - u(1)*u(1))*u(2) - u(1)

In MATLAB we can then solve the problem by

>> options = odeset('RelTol',0.0,'AbsTol',1e-6);

>> tspan = [0 30];

>> u0 = [2; 0]

>> [t, u] = ode45('myode', tspan, u0, options]);

Python¶

Calling up the vode method from the scipy library in Python also results in fairly compact code:

def f(t, u):

return [u[1], 3.*(1. - u[0]*u[0])*u[1] - u[0]]

from scipy.integrate import ode

r = ode(f).set_integrator('vode', method='adams',

order=10, rol=0, atol=1e-6,

with_jacobian=False)

u0 = [2.0, 0.0]

r.set_initial_value(u0, 0)

T = 30

dt = T/150.

u = []; t = []

while r.successful() and r.t <= T:

r.integrate(r.t + dt)

u.append(r.y); t.append(r.t)

Suppose you want to compare these methods and their implementations. This requires three different main programs, but even worse: three different implementations of the definition of the mathematical problem. Some specifications of \(f\) has the signature \(f(u,t)\) while others require \(f(t,u)\), and such differences between packages are often a cause of programming errors.

Odespy’s Unified Interface¶

The Odespy package provides a unified interface to all the three mentioned types of methods, which makes it easy to run all of them in a loop (program motivation.py):

def f(u, t):

return [u[1], 3.*(1. - u[0]*u[0])*u[1] - u[0]]

u0 = [2.0, 0.0]

import odespy, numpy

for method in odespy.Lsode, odespy.DormandPrince, odespy.Vode:

solver = method(f, rtol=0.0, atol=1e-6,

adams_or_bdf='adams', order=10)

solver.set_initial_condition(u0)

t_points = numpy.linspace(0, 30, 150)

u, t = solver.solve(t_points)

Note in particular that the same f and the same call syntax can be reused across methods and the underlying software.

Methods and Implementations Offered by Odespy¶

Odespy features a unified interface to the following collection of numerical methods and implementations:

- Pure Python implementations of classical explicit schemes such as the Forward Euler method (also called Euler); Runge-Kutta methods of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th order; Heun’s method; Adams-Bashforth methods of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th order; Adams-Bashforth-Moulton methods of 2nd and 3rd order.

- Pure Python implementations of classical implicit schemes such as Backward Euler; 2-step backward scheme; the \(\theta\) rule; the Midpoint (or Trapezoidal) method.

- Pure Python implementations of adaptive explicit Runge-Kutta methods of type Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg of order (4,5), Dormand-Prince of order (4,5), Cash-Karp of order (4,5), Bogacki-Shampine of order (2,3).

- Wrappers for all FORTRAN solvers in ODEPACK.

- Wrappers for the wrappers of FORTRAN solvers in scipy: vode and zvode (adaptive Adams or BDF from vode.f); dopri5 (adaptive Dormand-Prince method of order (4,5)); dop853 (adaptive Dormand-Prince method of order 8(5,3)); odeint (adaptive switching between Adams or BDF from the implementation LSODA in ODEPACK).

- Wrapper for the Runge-Kutta-Chebyshev formulas of order 2 as offered by the well-known FORTRAN code rkc.f.

- Wrapper for the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method of order (4,5) as provided by the well-known FORTRAN code rkf45.f.

- Wrapper for the Radau5 method as provided by the well-known FORTRAN code radau5.f.

- Wrapper for some solvers in the odelab package.

The ODE problem can always be specified in Python, but for wrappers of FORTRAN codes one can also implement the problem in FORTRAN and avoid callback to Python.

Installation¶

The Odespy package is most easily installed using pip:

sudo pip install -e \

git+https://github.com/hplgit/odespy.git#egg=odespy

Checking out the source code is almost as easy:

git clone git@github.com:hplgit/odespy.git

cd odespy

sudo python setup.py install

You will at least also need Python v2.7 and the numpy package. The FORTRAN codes rkc.f, rkf45.f, radau5.f, and ODEPACK comes with Odespy and are compiled and installed by setup.py. If you lack a FORTRAN compiler, you can drop the installation of the FORTRAN solvers by running

sudo python setup.py install --no-fortran

There have been various problems with compiling Odespy on Windows, usually related to the Fortran compiler. One recommended technique is to rely on Anaconda on Windows, install the ming32 compiler, and then run

Terminal> python setup.py install build --compiler=ming32

This may give problems of the type

File "C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\numpy\distutils\fcompiler\gnu.py",

line 333, in get_libraries

raise NotImplementedError(...)

NotImplementedError: Only MS compiler supported with gfortran on win64

A remedy is to edit the gnu.py file and comment out the NotImplementedError:

else:

#raise NotImplementedError("Only MS compiler ...")

pass

The Odespy package depends on several additional packages:

- scipy for running the Vode Adams/BDF solver, the Dormand-Prince adaptive methods Dop853, and Dopri5, and the scipy wrapper odeint of the FORTRAN code LSODA (Odespy features an alternative wrapper of the latter, in class Lsoda).

- sympy for running the extremely accurate odefun_sympy solver.

- odelab for accessing solvers in that package.

For plotting you will need matplotlib or scitools.

These packages are readily downloaded and installed by the standard setup.py script, as shown above. On Ubuntu and other Debian-based Linux systems the following line installs all that Odespy may need:

sudo apt-get install python-scipy python-nose python-sympy \

python-matplotlib python-scitools python-pip

The odelab package is installed by either

pip install -e git+https://github.com/olivierverdier/odelab#egg=odelab

or downloading the source and running setup.py:

git clone git://github.com/olivierverdier/odelab.git

cd odelab

sudo python setup.py install

Note

Despite Odespy’s many dependencies on other software, you can run the basic solvers implemented in pure Python without any additional software packages.

Basic Usage¶

This section explains how to use Odespy. The general principles and program steps are first explained. Thereafter, we present a series of examples with progressive complexity with respect to Python constructs and numerical methods.

Overview¶

A code using Odespy to solve ODEs consists of six steps. These are outlined in generic form below.

Step 1¶

Write the ODE problem in generic form \(u' = f(u, t)\), where \(u(t)\) is the unknown function to be solved for, or a vector of unknown functions of time in case of a system of ODEs.

Step 2¶

Implement the right-hand side function \(f(u, t)\) as a Python function f(u, t). The argument u is either a float object, in case of a scalar ODE, or a numpy array object, in case of a system of ODEs. Some solvers in this package also allow implementation of \(f\) in FORTRAN for increased efficiency.

Step 3¶

Create a solver object

solver = classname(f)

where classname is the name of a class in this package implementing the desired numerical method.

Many solver classes has a range of parameters that the user can set to control various parts of the solution process. The parameters are documented in the doc string of the class (pydoc classname will list the documentation in a terminal window). One can either specify parameters at construction time, via extra keyword arguments to the constructor,

solver = classname(f, prm1=value1, prm2=value2, ...)

or at any time using the set method:

solver.set(prm1=value1, prm2=value2, prm3=value3)

...

solver.set(prm4=value4)

Step 4¶

Set the initial condition \(u(0)=U_0\),

solver.set_initial_condition(U0)

where U0 is either a number, for a scalar ODE, or a sequence (list, tuple, numpy array), for a system of ODEs.

Step 5¶

Solve the ODE problem, which means to compute \(u(t)\) at some discrete user-specified time points \(t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_N\).

T = ... # end time

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

In case of a scalar ODE, the returned solution u is a one-dimensional numpy array where u[i] holds the solution at time point t[i]. For a system of ODEs, the returned u is a two-dimensional numpy array where u[i,j] holds the solution of the \(j\)-th unknown function at the \(i\)-th time point t[i] (\(u_j(t_i)\) in mathematics notation).

By giving the parameter disk_storage=True to the solver’s constructor, the returned u array is memory mapped (i.e., of type numpy.memmap) such that all the data are stored on file, but parts of the array can be efficiently accessed.

The time_points array specifies the time points where we want the solution to be computed. The returned array t is the same as time_points. The simplest numerical methods in the Odespy package apply the time_points array directly for the time stepping. That is, the time steps used are given by

time_points[i] - time_points[i-1] # i=0,1,...,len(time_points)-1

The adaptive schemes typically compute between each time point in the time_points array, making this array a specification where values of the unknowns are desired.

The solve method in solver classes also allows a second argument, terminate, which is a user-implemented Python function specifying when the solution process is to be terminated. For example, terminating when the solution reaches an asymptotic (known) value a can be done by

def terminate(u, t, step_no):

# u and t are arrays. Most recent solution is u[step_no].

tolerance = 1E-6

return abs(u[step_no] - a) < tolerance

u, t = solver.solve(time_points, terminate)

The arguments transferred to the terminate function are the solution array u, the corresponding time points t, and an integer step_no reflecting the most recently computed u value. That is, u[step_no] is most recently computed value of \(u\). (The array data u[step_no+1:] will typically be zero as these are uncomputed future values.)

Step 6¶

Extract solution components for plotting and further analysis. Since the u array returned from solver.solve stores all unknown functions at all discrete time levels, one usually wants to extract individual unknowns as one-dimensional arrays. Here is an example where unknown number \(0\) and \(k\) are extracted in individual arrays and plotted:

u_0 = u[:,0]

u_k = u[:,k]

from matplotlib.pyplot import plot, show

plot(t, u_0, t, u_k)

show()

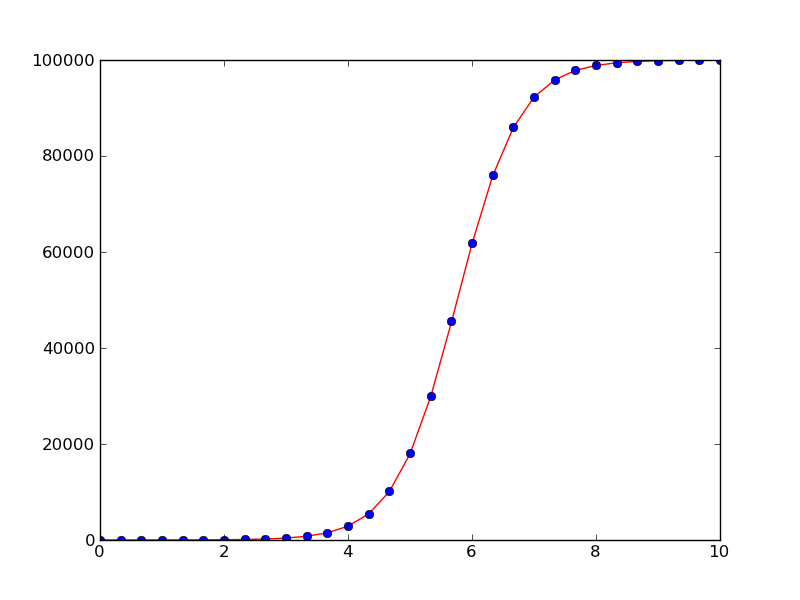

First Example: Logistic Growth¶

Our first example concerns the simple scalar ODE problem

where \(A>0\), \(a>0\), and \(R>0\) are known constants. This is a common model for population dynamics in ecology where \(u\) is the number of individuals, \(a\) the initial growth rate, \(R\) is the maximum number of individuals that the environment allows (the so-called carrying capacity of the environment).

Using a standard Runge-Kutta method of order four, the code for solving the problem in the time interval \([0,10]\) with \(N=30\) time steps, looks like this (program logistic1.py):

def f(u, t):

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

a = 2

R = 1E+5

A = 1

import odespy

solver = odespy.RK4(f)

solver.set_initial_condition(A)

from numpy import linspace, exp

T = 10 # end of simulation

N = 30 # no of time steps

time_points = linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

With the RK4 method and other non-adaptive methods the time steps are dictated by the time_points array. A constant time step of size is implied in the present example. Running an alternative numerical method just means replacing RK4 by, e.g., RK2, ForwardEuler, BackwardEuler, AdamsBashforth2, etc.

We can easily plot the numerical solution and compare with the exact solution (which is known for this equation):

def u_exact(t):

return R*A*exp(a*t)/(R + A*(exp(a*t) - 1))

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

plot(t, u, 'r-',

t, u_exact(t), 'bo')

savefig('tmppng'); savefig('tmp.pdf')

show()

Solution of the logistic equation with the 4-th order Runge-Kutta method (solid line) and comparison with the exact solution (dots)

All the examples in this tutorial are found in the GitHub directory https://github.com/hplgit/odespy/blob/master/doc/src/tutorial/src-odespy/. If you download the tarball or clone the GitHub repository, the examples reside in the directory doc/src/odespy/src-odespy.

Parameters in the Right-Hand Side Function¶

The right-hand side function and all physical parameters are often lumped together in a class, for instance,

class Logistic:

def __init__(self, a, R, A):

self.a = a

self.R = R

self.A = A

def f(self, u, t):

a, R = self.a, self.R # short form

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

def u_exact(self, t):

a, R, A = self.a, self.R, self.A # short form

return R*A*exp(a*t)/(R + A*(exp(a*t) - 1))

Note that introducing local variables like a and R, instead of using self.a and self.A, makes the code closer to the mathematics. This can be convenient when proof reading the implementation of complicated ODEs.

The numerical solution is computed by

import odespy

problem = Logistic(a=2, R=1E+5, A=1)

solver = odespy.RK4(problem.f)

solver.set_initial_condition(problem.A)

T = 10 # end of simulation

N = 30 # no of time steps

time_points = linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

The complete program is available in the file program logistic2.py.

Instead of having the problem parameters a and R in the ODE as global variables or in a class, we may include them as extra arguments to f, either as positional arguments or as keyword arguments. Positional arguments can be sent to f via the constructor argument f_args (a list/tuple of variables), while a dictionary f_kwargs is used to transfer keyword arguments to f via the constructor. Here is an example on using keyword arguments:

def f(u, t, a=1, R=1):

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

A = 1

import odespy

solver = odespy.RK4(f, f_kwargs=dict(a=2, R=1E+5))

In general, a mix of positional and keyword arguments can be used in f:

def f(u, t, arg1, arg2, arg3, ..., kwarg1=val1, kwarg2=val2, ...):

...

solver = odespy.classname(f,

f_args=[arg1, arg2, arg3, ...],

f_kwargs=dict(kwarg1=val1, kwarg2=val2, ...))

# Alternative setting of f_args and f_kwargs

solver.set(f_args=[arg1, arg2, arg3, ...],

f_kwargs=dict(kwarg1=val1, kwarg2=val2, ...))

Solvers will call f as f(u, t, *f_args, **f_kwargs).

Continuing a Previous Simulation¶

It is easy to simulate for some time interval \([0, T_1]\), then continue with \(u(T_1)\) as new initial condition and simulate for \(t\) in \([T_1, T_2]\) and so on. Let us divide the time domain into subdomains and compute the solution for each subdomain in sequence. The following program performs the steps (logistic4.py).

def f(u, t, a=1, R=1):

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

A = 1

import odespy, numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import plot, hold, show, axis

solver = odespy.RK4(f, f_kwargs=dict(a=2, R=1E+5))

# Split time domain into subdomains and

# integrate the ODE in each subdomain

T = [0, 1, 4, 8, 12] # subdomain boundaries

N_tot = 30 # total no of time steps

dt = float(T[-1])/N_tot # time step, kept fixed

u = []; t = [] # collectors for u and t in each domain

for i in range(len(T)-1):

T_interval = T[i+1] - T[i]

N = int(round(T_interval/dt))

time_points = numpy.linspace(T[i], T[i+1], N+1)

solver.set_initial_condition(A) # at time_points[0]

print 'Solving in [%s, %s] with %d intervals' % \

(T[i], T[i+1], N)

ui, ti = solver.solve(time_points)

A = ui[-1] # newest ui value is next initial condition

plot(ti, ui)

hold('on')

u.append(ui); t.append(ti)

axis([0, T[-1], -0.1E+5, 1.1E+5])

# Can concatenate all the elements of u and t, if desired

u = numpy.concatenate(u); t = numpy.concatenate(t)

savefig('tmppng'); savefig('tmp.pdf')

Termination Criterion for the Simulation¶

We know that the solution \(u\) of the logistic equation approaches \(R\) as \(t\rightarrow\infty\). Instead of using a trial and error process for determining an appropriate time integral for integration, the solver.solve method accepts a user-defined function terminate that can be used to implement a criterion for terminating the solution process. Mathematically, the relevant criterion is \(||u-R|| < \hbox{tol}\), where tol is an acceptable tolerance, say \(100\) in the present case where \(R=10^5\). The terminate function implements the criterion and returns true if the criterion is met:

def terminate(u, t, step_no):

"""u[step_no] holds (the most recent) solution at t[step_no]."""

return abs(u[step_no] - R) < tol

Note that the simulation is anyway stopped for \(t > T\) so \(T\) must be large enough for the termination criterion to be reached (if not, a warning will be issued). With a terminate function it is also convenient to specify the time step dt and not the total number of time steps.

A complete program can be as follows (logistic5.py):

def f(u, t):

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

a = 2

R = 1E+5

A = 1

import odespy, numpy

solver = odespy.RK4(f)

solver.set_initial_condition(A)

T = 20 # end of simulation

dt = 0.25

N = int(round(T/dt))

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

tol = 100 # tolerance for termination criterion

def terminate(u, t, step_no):

"""u[step_no] holds (the most recent) solution at t[step_no]."""

return abs(u[step_no] - R) < tol

u, t = solver.solve(time_points, terminate)

print 'Final u(t=%g)=%g' % (t[-1], u[-1])

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

plot(t, u, 'r-')

savefig('tmppng'); savefig('tmp.pdf')

show()

A Class-Based Implementation¶

The previous code example can be recast into a more class-based (“object-oriented programming”) example. We lump all data related to the problem (the “physics”) into a problem class Logistic, while all data related to the numerical solution and its quality are taken care of by class Solver. The code below illustrates the ideas (logistic6.py):

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import odespy

class Logistic:

def __init__(self, a, R, A, T):

"""

a` is (initial growth rate), `R` the carrying capacity,

`A` the initial amount of u, and `T` is some (very) total

simulation time when `u` is very close to the asymptotic

value `R`.

"""

self.a, self.R, self.A = a, R, A

self.tol = 0.01*R # tolerance for termination criterion

def f(self, u, t):

"""Right-hand side of the ODE."""

a, R = self.a, self.R # short form

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

def terminate(self, u, t, step_no):

"""u[step_no] holds solution at t[step_no]."""

return abs(u[step_no] - self.R) < self.tol

def u_exact(self, t):

a, R, A = self.a, self.R, self.A # short form

return R*A*np.exp(a*t)/(R + A*(np.exp(a*t) - 1))

class Solver:

def __init__(self, problem, dt, method='RK4'):

self.problem = problem

self.dt = dt

self.method_class = eval('odespy.' + method)

self.N = int(round(T/dt))

def solve(self):

self.solver = self.method_class(self.problem.f)

self.solver.set_initial_condition(self.problem.A)

time_points = np.linspace(0, self.problem.T, self.N+1)

self.u, self.t = self.solver.solve(

time_points, self.problem.terminate)

print 'Final u(t=%g)=%g' % (t[-1], u[-1])

def plot(self):

plt.plot(self.t, self.u, 'r-',

self.t, self.u_exact(self.t), 'bo')

plt.legend(['numerical', 'exact'])

plt.savefig('tmp.png'); plt.savefig('tmp.pdf')

plt.show()

def main():

problem = Logistic(a=2, R=1E+5, A=1, T=20)

solver = Solver(problem, dt=0.25, method='RK4')

solver.solve()

solver.plot()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Using Other Symbols¶

The Odespy package applies u for the unknown function or vector of unknown functions and t as the name of the independent variable. Many problems involve other symbols for functions and independent variables. These symbols should be reflected in the user’s code. For example, here is a coding example involving the logistic equation written as \(y'(x)=au(x)(1-u(x)/R(x))\), where now a variable \(R=R(x)\) is considered. Following the setup from the very first program above solving the logistic ODE, we can easily introduce our own nomenclature (logistic7.py):

def f(y, x):

return a*y*(1 - y/R)

a = 2; R = 1E+5; A = 1

import odespy, numpy

solver = odespy.RK4(f)

solver.set_initial_condition(A)

L = 10 # end of x domain

N = 30 # no of time steps

x_points = numpy.linspace(0, L, N+1)

y, x = solver.solve(x_points)

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

plot(x, y, 'r-')

xlabel('x'); ylabel('y')

show()

As shown, we use y for u, x for t, and x_points instead of time_points.

Example: Solving an ODE System¶

We shall now explain how to solve a system of ODEs using a scalar second-order ODE as starting point. The angle \(\theta\) of a pendulum with mass \(m\) and length \(L\) is governed by the equation (neglecting air resistance for simplicity)

A dot over \(\theta\) implies differentiation with respect to time. The ODE can be written as \(\ddot\theta + c\sin\theta=0\) by introducing \(c = g/L\).

This problem must be expressed as a first-order ODE system if it is going to be solved by the tools in the Odespy package. Introducing \(\omega = \dot\theta\) (the angular velocity) as auxiliary unknown, we get the system

with \(\theta(0)=\Theta\) and \(\omega(0)=0\).

Now the f function must return a list or array with the two right-hand side functions:

def f(u, t):

theta, omega = u

return [omega, -c*sin(theta)]

Note that when we have a system of ODEs with n components, the u object sent to the f function is an array of length n, representing the value of all components in the ODE system at time t. Here we extract the two components of u in separate local variables with names equal to what is used in the mathematical description of the current problem.

The initial conditions must be specified as a list:

solver = odespy.Heun(f)

solver.set_initial_condition([Theta, 0])

To specify the time points we here first decide on a number of periods (oscillations back and forth) to simulate and then on the time resolution of each period. Note that when \(\Theta\) is small we can replace \(\sin\theta\) by \(\theta\) and find an analytical solution \(\theta (t)=\Theta\cos\left(\sqrt{c}t\right)\) whose period is \(2\pi/\sqrt{c}\). We use this expression as an approximation for the period also when \(\Theta\) is not small.

freq = sqrt(c) # frequency of oscillations when Theta is small

period = 2*pi/freq # the period of the oscillations

T = 10*period # final time

N_per_period = 20 # resolution of one period

N = N_per_period*period

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

The u returned from solver.solve is a two-dimensional array, where the columns hold the various solution functions of the ODE system. That is, the first column holds \(\theta\) and the second column holds \(\omega\). For convenience we extract the individual solution components in individual arrays:

theta = u[:,0]

omega = u[:,1]

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

plot(t, theta, 'r-')

savefig('tmppng'); savefig('tmp.pdf')

show()

The complete program is available in the file osc1a.py.

Looking at the plot reveals that the numerical solution has an alarming feature: the amplitude grows (indicating increasing energy in the system). Changing T to 28 periods instead of 10 makes the numerical solution explode. The increasing amplitude is a numerical artifact that some of the simple solution methods suffer from.

Using a more sophisticated method, say the 4-th order Runge-Kutta method, is just a matter of substituting Heun by RK4:

solver = odespy.RK4(f)

solver.set_initial_condition([Theta, 0])

freq = sqrt(c) # frequency of oscillations when Theta is small

period = 2*pi/freq # the period of the oscillations

T = 10*period # final time

N_per_period = 20 # resolution of one period

N = N_per_period*period

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

theta = u[:,0]

omega = u[:,1]

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

plot(t, theta, 'r-')

savefig('tmppng'); savefig('tmp.pdf')

show()

The amplitude now becomes (almost) constant in time as expected. Another very good and popular method for this problem is presented next.

The Euler-Cromer Method¶

Physicists will most likely solve the model problem in the section Example: Solving an ODE System by the Euler-Cromer method. For a single degree of freedom system,

typically modeling an oscillatory system, the Euler-Cromer method writes the system as two ODEs,

A Forward Euler scheme is used for the first equation, while a Backward Euler scheme is used for the second:

The two first-order methods used in this symmetric fashion results in a second-order method that will preserve the amplitude of the oscillations.

For general multi degree of freedom systems, we have some vector ODE arising from, typically, Newton’s second law of motion,

This is rewritten as

and discretized as

The convention in Odespy is to group all the unknowns as velocity and position for each degree of freedom. That is, if the component form of \(\boldsymbol{r}\) and \(\boldsymbol{v}\) is written as

the \(u\) vector of all unknowns in the Euler-Cromer method in Odespy must be

The corresponding set of ODEs are

For the particular case of a pendulum we write our system as

and let \(u=(\omega, \theta)\). The relevant right-hand side function becomes

def f(u, t):

omega, theta = u

return [-c*sin(theta), omega]

With some imports,

import odespy

from numpy import *

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

we can write the rest of the program in a standard fashion:

c = 1

Theta0_degrees = 30

solver = odespy.EulerCromer(f)

Theta0 = Theta0_degrees*pi/180

solver.set_initial_condition([0, Theta0])

# Solve for num_periods periods using formulas for small theta

freq = sqrt(c) # frequency of oscillations

period = 2*pi/freq # one period

N = 40 # intervals per period

dt = period/N # time step

num_periods = 10

T = num_periods*period # total simulation time

time_points = linspace(0, T, num_periods*N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

# Extract components and plot theta

theta = u[:,1]

omega = u[:,0]

theta_linear = lambda t: Theta0*cos(sqrt(c)*t)

plot(t, theta, t, theta_linear(t))

legend(['Euler-Cromer', 'Linearized problem'], loc='lower left')

With \(\Theta_0\) as 30 degrees, the fully nonlinear solution is slightly out of phase with the solution of the linearized problem \(\ddot\theta + c\theta =0\), see Figure Euler-Cromer method applied to the pendulum problem. As \(\Theta_0\rightarrow 0\), the two curves approach each other. The Euler-Cromer method is significantly better than Heun’s method used in the previous section and reproduces the exact amplitude.

Testing Several Methods¶

[hpl 1: After Euler-Cromer, change the order of the ODEs and unknowns!]

We shall now make a more advanced solver by extending the pendulum example. More specifically, we shall

- represent the right-hand side function as class,

- compare several different solvers,

- compute error of numerical solutions.

Since we want to compare numerical errors in the various solvers we need a test problem where the exact solution is known. Approximating \(\sin(\theta)\) by \(\theta\) (valid for small \(\theta\)), gives the ODE system

with \(\theta(0)=\Theta\) and \(\omega(0)=0\).

Right-hand side functions with parameters can be handled by including extra arguments via the f_args and f_kwargs functionality, or by using a class where the parameters are attributes and an f method defines \(f(u,t)\). The section Parameters in the Right-Hand Side Function exemplifies the details. A minimal class representation of the right-hand side function in the present case looks like this:

class Problem:

def __init__(self, c, Theta):

self.c, self.Theta = float(c), float(Theta)

def f(self, u, t):

theta, omega = u; c = self.c

return [omega, -c*theta]

problem = Problem(c=1, Theta=pi/4)

It would be convenient to add an attribute period which holds an estimate of the period of oscillations as we need this for deciding on the complete time interval for solving the differential equations. An appropriate extension of class Problem is therefore

class Problem:

def __init__(self, c, Theta):

self.c, self.Theta = float(c), float(Theta)

self.freq = sqrt(c)

self.period = 2*pi/self.freq

def f(self, u, t):

theta, omega = u; c = self.c

return [omega, -c*theta]

problem = Problem(c=1, Theta=pi/4)

The second extension is to loop over many solvers. All solvers can be listed by

>>> import odespy

>>> methods = list_all_solvers()

>>> for method in methods:

... print method

...

AdamsBashMoulton2

AdamsBashMoulton3

AdamsBashforth2

...

Vode

lsoda_scipy

odefun_sympy

odelab

A similar function, list_available_solvers, returns a list of the names of the solvers that are available in the current installation (e.g., the Vode solver is only available if the comprehensive scipy package is installed). This is the list that is usually most relevant.

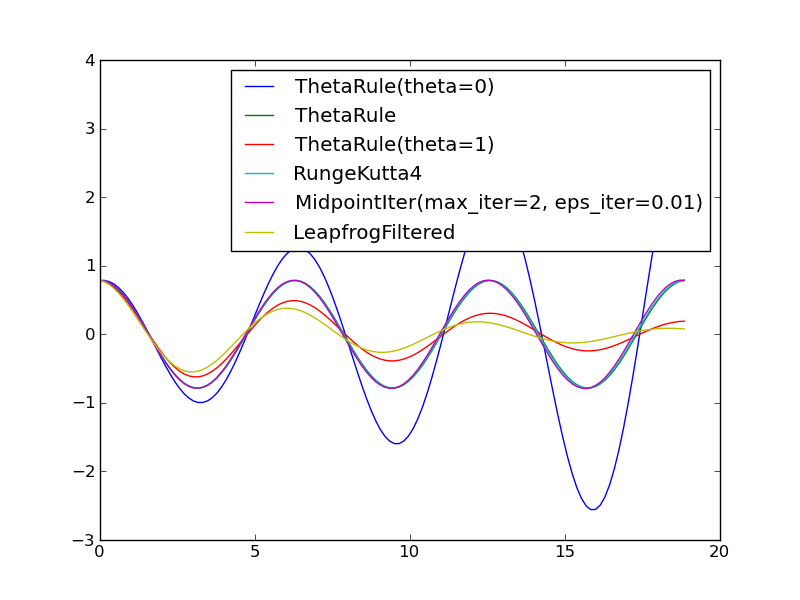

For now we explicitly choose a subset of the commonly available solvers:

import odespy

solvers = [

odespy.ThetaRule(problem.f, theta=0), # Forward Euler

odespy.ThetaRule(problem.f, theta=0.5), # Midpoint method

odespy.ThetaRule(problem.f, theta=1), # Backward Euler

odespy.RK4(problem.f),

odespy.MidpointIter(problem.f, max_iter=2, eps_iter=0.01),

odespy.LeapfrogFiltered(problem.f),

]

To see what a method is and its arguments to the constructor, invoke the doc string of the class, e.g., help(ThetaRule) inside a Python shell like IPython, or run pydoc odespy.ThetaRule in a terminal window, or invoke the Odespy API documentation.

It will be evident that the ThetaRule solver with theta=0 and theta=1 (Forward and Backward Euler methods) gives growing and decaying amplitudes, respectively, while the other solvers are capable of reproducing the constant amplitude of the oscillations of in the current mathematical model.

The loop over the chosen solvers may look like

N_per_period = 20

T = 3*problem.period # final time

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

legends = []

for solver in solvers:

solver_name = str(solver) # short description of solver

print solver_name

solver.set_initial_condition([problem.Theta, 0])

N = N_per_period*problem.period

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

theta = u[:,0]

legends.append(solver_name)

plt.plot(t, theta)

plt.hold('on')

plt.legend(legends)

plotfile = __file__[:-3]

plt.savefig(plotfile + '.png'); plt.savefig(plotfile + '.pdf')

plt.show()

A complete program is available as osc2.py.

We can extend this program to compute the error in each numerical solution for different time step sizes. Let results be a dictionary with the method name as key, containing two sub dictionaries dt and error, which hold a sequence of time steps and a sequence of corresponding errors, respectively. The errors are computed by subtracting the numerical solution from the exact solution,

theta_exact = lambda t: problem.Theta*numpy.cos(sqrt(problem.c)*t)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

theta = u[:,0]

error = numpy.abs(theta_exact(t) - theta)

The so-called L2 norm of the error array is a suitable scalar error measure (square root of total error squared and integrated, here numerically):

error_L2 = sqrt(numpy.sum(error**2)/dt)

where dt is the time step size.

Typical loops over solvers and resolutions look as follows (osc3.py):

try:

num_periods = int(sys.argv[1])

except IndexError:

num_periods = 8 # default

T = num_periods*problem.period # final time

results = {}

resolutions = [10, 20, 40, 80, 160] # intervals per period

import numpy

for solver in solvers:

solver_name = str(solver)

results[solver_name] = {'dt': [], 'error': []}

solver.set_initial_condition([problem.Theta, 0])

for N_per_period in resolutions:

N = N_per_period*num_periods

time_points = numpy.linspace(0, T, N+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

theta = u[:,0]

error = numpy.abs(theta_exact(t) - theta)

error_L2 = sqrt(numpy.sum(error**2)/N)

if not numpy.isnan(error_L2): # drop nan (overflow)

results[solver_name]['dt'].append(t[1] - t[0])

results[solver_name]['error'].append(error_L2)

Assuming the error to be of the form \(C\Delta t^r\), we can estimate \(C\) and \(r\) from two consecutive experiments to obtain a sequence of \(r\) values which (hopefully) convergences to a value that we can view as the empirical convergence rate of a method. Given the sequence of time steps and errors, we can compare two experiments \(i\) and \(i-1\), with errors \(E_{i}=C\Delta t_i^r\), and estimate \(r=\ln(E_i/E_{i-1})/\ln(\Delta t_i/\Delta t_{i-1})\):

from math import log

print '\n\nConvergence results for %d periods' % num_periods

for solver_name in results:

r_h = results[solver_name]['dt']

r_E = results[solver_name]['error']

rates = [log(r_E[i]/r_E[i-1])/log(r_h[i]/r_h[i-1]) for i

in range(1, len(r_h))]

# Reformat rates with 1 decimal for rate

rates = ', '.join(['%.1f' % rate for rate in rates])

print '%-20s r: %s E_min=%.1E' % \

(solver_name, rates, min(results[solver_name]['error']))

With 4 periods we get

ThetaRule(theta=0) r: 4.2, 2.4, 1.7, 1.3 E_min=1.9E-01

LeapfrogFiltered r: 10.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 E_min=1.8E-01

ThetaRule(theta=1) r: 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 E_min=1.3E-01

ThetaRule r: 2.3, 2.0, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=2.1E-03

RK4 r: 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0 E_min=1.6E-07

Leapfrog r: 2.2, 2.0, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=2.1E-03

RK2 r: 2.3, 2.0, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=2.1E-03

MidpointIter r: 2.0, 1.0, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=2.1E-03

The rates of the Forward and Backward Euler methods (1st and 3rd line) have not yet converged to unity, as expected, while the 2nd-order Runge-Kutta method, Leapfrog, and the \(\theta\) rule with \(\theta =0.5\) (ThetaRule with default value of theta) shows the expected \(r=2\) value. The 4th-order Runge-Kutta holds the promise of being of 4th order, while the filtered Leapfrog method has slow convergence and a fairly large error, which is also evident in the previous figure.

Extending the time domain to 20 periods makes many of the simplest methods inaccurate and the rates computed on coarse time meshes are irrelevant. Also in this case, three of the methods are useless, while the others deliver their promised convergence rates (Forward Euler, i.e., ThetaRule with theta=0 is left out because of ridiculous results):

LeapfrogFiltered r: 63.7, 0.0, 0.1, 0.2 E_min=4.3E-01

ThetaRule(theta=1) r: 0.0, 0.1, 0.1, 0.3 E_min=3.8E-01

ThetaRule r: 3.7, 2.1, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=1.0E-02

RK4 r: 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0 E_min=8.0E-07

Leapfrog r: 0.5, 1.9, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=1.0E-02

RK2 r: 3.7, 2.1, 2.0, 2.0 E_min=1.0E-02

MidpointIter r: 1.8, 0.8, 1.9, 2.0 E_min=1.0E-02

More Advanced Implementations¶

Make a Subclass of Class Problem¶

Odespy features a module problems for defining ODE problems. There is a superclass Problem in this module defining what we expect of information about an ODE problem, as well as some convenience functions that are inherited in subclasses. A rough sketch of class Problem is listed here:

class Problem:

stiff = False # classification of the problem is stiff or not

complex_ = False # True if f(u,t) is complex valued

not_suitable_solvers = [] # list solvers that should be be used

short_description = '' # one-line problem description

def __init__(self):

pass

def __contains__(self, attr):

"""Return True if attr is a method in instance self."""

def terminate(self, u, t, step_number):

"""Default terminate function, always returning False."""

return False

def default_parameters(self):

"""

Compute suitable time_points, atol/rtol, etc. for the

particular problem. Useful for quick generation of test

cases, demos, unit tests, etc.

"""

return {}

def u_exact(self, t):

"""Implementation of the exact solution."""

return None

Subclasses of Problem typically implements the constructor, for registering parameters in the ODE and the initial condition, and a method f for defining the right-hand side. For implicit solution method we may provide a method jac returning the Jacobian of \(f(u,t)\) with respect to \(u\). Some problems may also register an analytical solution in u_exact. Here is an example of implementing the logistic ODE from the section First Example: Logistic Growth:

import odespy

class Logistic(odespy.problems.Problem):

short_description = "Logistic equation"

def __init__(self, a, R, A):

self.a = a

self.R = R

self.U0 = A

def f(self, u, t):

a, R = self.a, self.R # short form

return a*u*(1 - u/R)

def jac(self, u, t):

a, R = self.a, self.R # short form

return a*(1 - u/R) + a*u*(1 - 1./R)

def u_exact(self, t):

a, R, U0 = self.a, self.R, self.U0 # short form

return R*U0*numpy.exp(a*t)/(R + U0*(numpy.exp(a*t) - 1))

The stiff, complex_, and not_suitable_solvers class variables can just be inherited. Note that u_exact should work for a vector t so numpy versions of mathematical functions must be used.

The initial condition is by convention stored as the attribute U0 in a subclass of Problem, and specified as argument to the constructor.

Here are the typical steps when using such a problem class:

problem = Logistic(a=2, R=1E+5, A=1)

solver = odespy.RK4(problem.f)

solver.set_initial_condition(problem.U0)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

The problem class may also feature additional methods:

class MyProblem(odespy.problems.Problem)

...

def constraints(self, u, t):

"""Python function for additional constraints: g(u,t)=0."""

def define_command_line_arguments(self, parser):

"""

Initialize an argparse object for reading command-line

option-value pairs. `parser` is an ``argparse`` object.

"""

def verify(self, u, t, atol=None, rtol=None):

"""

Return True if u at time points t coincides with an exact

solution within the prescribed tolerances. If one of the

tolerances is None, return max computed error (infinity

norm). Return None if the solution cannot be verified.

"""

The module odespy.problems contains many predefined ODE problems.

Example: Solving a Complex ODE Problem¶

Many of the solvers offered by Odespy can deal with complex-valued ODE problems. Consider

where \(i=\sqrt{-1}\) is the imaginary unit. The right-hand side is implemented as 1j*w*u in Python since Python applies j as the imaginary unit in complex numbers.

Quick Implementation¶

For complex-valued ODEs, i.e., complex-valued right-hand side functions or initial conditions, the argument complex_valued=True must be supplied to the constructor. A complete program reads

def f(u, t):

return 1j*w*u

import odespy, numpy

w = 2*numpy.pi

solver = odespy.RK4(f, complex_valued=True)

solver.set_initial_condition(1+0j)

u, t = solver.solve(numpy.linspace(0, 6, 101))

The function odespy.list_not_suitable_complex_solvers() returns a list of all the classes in Odespy that are not suitable for complex-valued ODE problems.

Comparison of Methods¶

We can try three classes that do work for complex-valued ODEs: Vode, RK4, and RKFehlberg. Comparing these with respect to CPU time and final error for a very long time integration of 600 periods is carried out by the following program.

def f(u, t):

return 1j*w*u

import odespy, numpy, time

w = 2*numpy.pi

n = 600 # no of periods

r = 40 # resolution of each period

tp = numpy.linspace(0, n, n*r+1)

solvers = [odespy.Vode(f, complex_valued=True,

atol=1E-7, rtol=1E-6,

adams_or_bdf='adams'),

odespy.RK4(f, complex_valued=True),

odespy.RKFehlberg(f, complex_valued=True,

atol=1E-7, rtol=1E-6)]

cpu = []

for solver in solvers:

solver.set_initial_condition(1+0j)

t0 = time.clock()

solver.solve(tp)

t1 = time.clock()

cpu.append(t1-t0)

# Compare solutions at the end point:

exact = numpy.exp(1j*w*tp).real[-1]

min_cpu = min(cpu); cpu = [c/min_cpu for c in cpu] # normalize

print 'Exact: u(%g)=%g' % (tp[-1], exact)

for solver, cpu_time in zip(solvers, cpu):

print '%-15s u(%g)=%.6f (error: %10.2E, cpu: %.1f)' % \

(solver.__class__.__name__,

solver.t[-1], solver.u[-1].real,

exact - solver.u[-1].real, cpu_time)

We remark that the solution and the corresponding time values can always be recovered as solver.u and solver.t, respectively.

The output from the program may read

Exact: u(600)=1

Vode u(600)=1.001587 (error: -1.59E-03, cpu: 1.0)

RK4 u(600)=0.997328 (error: 2.67E-03, cpu: 1.3)

RKFehlberg u(600)=1.000953 (error: -9.53E-04, cpu: 7.5)

The Vode solver is a wrapper of the FORTRAN code zvode.f in scipy.integrate.ode and is an adaptive Adams method (with default settings, as used here), RK4 is a compact and straightforward Runge-Kutta method of order 4 in pure Python with constant step size, and RKFehlberg is a pure Python implementation of the adaptive Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method of order (4,5). These methods give approximately the same final error, but with different CPU times. We observe that the very simple RK4 solver in pure Python compares favorably with the much more sophisticated FORTRAN subroutine zvode.

Avoiding Callbacks to Python¶

The ODE solvers that are implemented in FORTRAN calls, by default, the user’s Python implementation of \(f(u,t)\). Making many calls from FORTRAN to Python may introduce significant overhead and slow down the solution process. When the algorithm is implemented in FORTRAN we should also implement the right-hand side in FORTRAN and call this right-hand side subroutine directly. Odespy offers this possibility.

The idea is that the user writes a FORTRAN subroutine defining \(f(u,t)\). Thereafter, f2py is used to make this subroutine callable from Python. If we specify the Python interface to this subroutine as an f_f77 argument to the solver’s constructor, the Odespy class will make sure that no callbacks to the \(f(u,t)\) definition go via Python.

The Logistic ODE¶

Here is a minimalistic example involving the logistic ODE from the section First Example: Logistic Growth. The FORTRAN implementation of \(f(u,t)\) is more complicated than the Python counterpart. The subroutine has the signature

subroutine f_f77(neq, t, u, udot)

Cf2py intent(hide) neq

Cf2py intent(out) udot

integer neq

double precision t, u, udot

dimension u(neq), udot(neq)

This means that there are two additional arguments: neq for the number of equations in the ODE system, and udot for the array of \(f(u,t)\) that is output from the subroutine.

We write the FORTRAN implementation of \(f(u,t)\) in a string:

a = 2

R = 1E+5

f_f77_str = """

subroutine f_f77(neq, t, u, udot)

Cf2py intent(hide) neq

Cf2py intent(out) udot

integer neq

double precision t, u, udot

dimension u(neq), udot(neq)

udot(1) = %.3f*u(1)*(1 - u(1)/%.1f)

return

end

""" % (a, R)

Observe that we can transfer problem parameters to the FORTRAN subroutine by writing their values directly into the FORTRAN source code. The other alternative would be to transfer the parameters as global (COMMON block) variables to the FORTRAN code, which is technically much more complicated. Also observe that we need to deal with udot and u as arrays even for a scalar ODE.

Using f2py to compile the string into a Python module is automated by the odespy.compile_f77 function:

import odespy

f_f77 = odespy.compile_f77(f_f77_str)

The returned object f_f77 is a callable object that allows the FORTRAN subroutine to be called as udot = f_f77(t, u) from Python. (However, the Odespy solvers will not use f_f77 directly, but rather its function pointer to the FORTRAN subroutine, and transfer this pointer to the FORTRAN solver. The switching between t, u and u, t arguments is taken care of. All necessary steps are automatically done behind the scene.)

The solver can be declared as

solver = odespy.Lsode(f=None, f_f77=f_f77)

Several solvers accept FORTRAN definitions of the right-hand side: Lsode, Lsoda, and the other ODEPACK solvers, RKC, RKF45, Radau5. Look up the documentation of their f_f77 parameter to see exactly what arguments and conventions that the FORTRAN subroutine demand.

The file logistic10.py contains a complete program for solving the logistic ODE with \(f(u,t)\) implemented in Fortran.

Implementing the van der Pol Equation in FORTRAN¶

As a slightly more complicated example, also involving a subclass of Problem and computation of the Jacobian and \(f(u,t)\) in FORTRAN, we consider the van der Pol equation,

written as a system as shown in the section ode:sec:motivation. We start by implementing a problem class with Python code for \(f(u,t)\) and its Jacobian:

import odespy

class VanDerPolOscillator(odespy.problems.Problem):

short_description = "Van der Pol oscillator"

def __init__(self, U0=[2, 1], mu=3.):

self.U0 = U0

self.mu = mu

def f(self, u, t):

u_0, u_1 = u

mu = self.mu

return [u_1, mu*(1 - u_0**2)*u_1 - u_0]

def jac(self, u, t):

u_0, u_1 = u

mu = self.mu

return [[0., 1.],

[-2*mu*u_0*u_1 - 1, mu*(1 - u_0**2)]]

Now, we want to provide f and jac in FORTRAN as well. The FORTRAN code for \(f(u,t)\) can be returned from a method:

class VanDerPolOscillator(odespy.problems.Problem):

...

def str_f_f77(self):

"""Return f(u,t) as Fortran source code string."""

return """

subroutine f_f77(neq, t, u, udot)

Cf2py intent(hide) neq

Cf2py intent(out) udot

integer neq

double precision t, u, udot

dimension u(neq), udot(neq)

udot(1) = u(2)

udot(2) = %g*(1 - u(1)**2)*u(2) - u(1)

return

end

""" % self.mu

While all FORTRAN solvers supported by Odespy so far employ the same signature for the \(f(u,t)\) function, different solvers apply different signatures for the Jacobian. Here are two versions for ODEPACK and Radau5, respectively:

class VanDerPolOscillator(odespy.problems.Problem):

...

def str_jac_f77_fadau5(self):

return """

subroutine jac_f77_radau5(neq,t,u,dfu,ldfu,rpar,ipar)

Cf2py intent(hide) neq,rpar,ipar

Cf2py intent(in) t,u,ldfu

Cf2py intent(out) dfu

integer neq,ipar,ldfu

double precision t,u,dfu,rpar

dimension u(neq),dfu(ldfu,neq),rpar(*),ipar(*)

dfu(1,1) = 0

dfu(1,2) = 1

dfu(2,1) = -2*%g*u(1)*u(2) - 1

dfu(2,2) = %g*(1-u(1)**2)

return

end

""" % (self.mu, self.mu)

def str_jac_f77_lsode_dense(self):

return """

subroutine jac_f77(neq, t, u, ml, mu, pd, nrowpd)

Cf2py intent(hide) neq, ml, mu, nrowpd

Cf2py intent(out) pd

integer neq, ml, mu, nrowpd

double precision t, u, pd

dimension u(neq), pd(nrowpd,neq)

pd(1,1) = 0

pd(1,2) = 1

pd(2,1) = -2*%g*u(1)*u(2) - 1

pd(2,2) = %g*(1 - u(1)**2)

return

end

""" % (self.mu, self.mu)

For the Lsode solver we can also provide the Jacobian in banded matrix format (this is not yet supported for Radau5, but the underlying FORTRAN code allows a banded Jacobian).

Having some methods returning FORTRAN code, we need to turn the source code into Python modules. This is done by odespy.compile_f77 in the constructor of class VanDerPolOscillator:

class VanDerPolOscillator(odespy.problems.Problem):

def __init__(self, U0=[2, 1], mu=3.):

self.U0 = U0

self.mu = mu

# Compile F77 functions

self.f_f77, self.jac_f77_radau5, self.jac_f77_lsode = \

compile_f77([self.str_f_f77(),

self.str_jac_f77_radau5(),

self.str_jac_f77_lsode()])

The application of this problem class goes as follows:

problem = VanDerPolOscillator()

import odespy

solver = odespy.Radau5(f=None, f=problem.f_f77,

jac=problem.jac_f77_radau5)

solver.set_initial_condition(problem.U0)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

Example: Solving a Stochastic Differential Equation¶

We consider an oscillator driven by stochastic white noise:

where \(N(t)\) is the white noise function computed numerically as

where \(\Delta W_1,\Delta W_2,\ldots\) are independent normally distributed random variables with mean zero and unit standard deviation, and \(\sigma\) is the strength of the noise. The physical feature of this problem is that \(N(t)\) provides an excitation containing “all” frequencies, but the oscillator is a strong filter: with low damping one of the frequencies in \(N(t)\) will hit the resonance frequency \(\sqrt{c}/(2\pi)\) which will then dominate the output signal \(x(t)\).

The noise is additive in this stochastic differential equation so there is no difference between the Ito and Stratonovich interpretations of the equation.

The challenge with this model problem is that stochastic differential equations do not fit with the user interface offered by Odespy, since the right-hand side function is assumed to be dependent only on the solution and the present time (f(u,t)), and additional user-defined parameters, but for the present problem the right-hand side function needs information about \(N(t)\) and hence the size of the current time step.

We can solve this issue by having a reference to the solver in the right-hand side function, precomputing \(N(t_i)\) for all time intervals \(i\), and using the n attribute in the solver for selecting the right force term (recall that some methods will call the right-hand side function many times during a time interval - all these calls must use the same value of the white noise).

The right-hand side function must do many things so a class is appropriate:

class WhiteNoiseOscillator:

def __init__(self, b, c, sigma=1):

self.b, self.c, self.sigma = b, c, sigma

def connect_solver(self, solver):

"""Solver is needed for time step number and size."""

self.solver = solver

def f(self, u, t):

if not hasattr(self, 'N'): # is self.N not yet computed?

# Compute N(t) for all time intervals

import numpy

numpy.random.seed(12)

t = self.solver.t

dW = numpy.random.normal(loc=0, scale=1, size=len(t)-1)

dt = t[1:] - t[:-1]

self.N = self.sigma*dW/numpy.sqrt(dt)

x, v = u

N = self.N[self.solver.n]

return [v, N -self.b*v -self.c*x]

Note that \(N(t)\) is computed on demand the first time the right-hand side function is called. We need to wait until the f method is called since we need access to the solver instance to compute the self.N array.

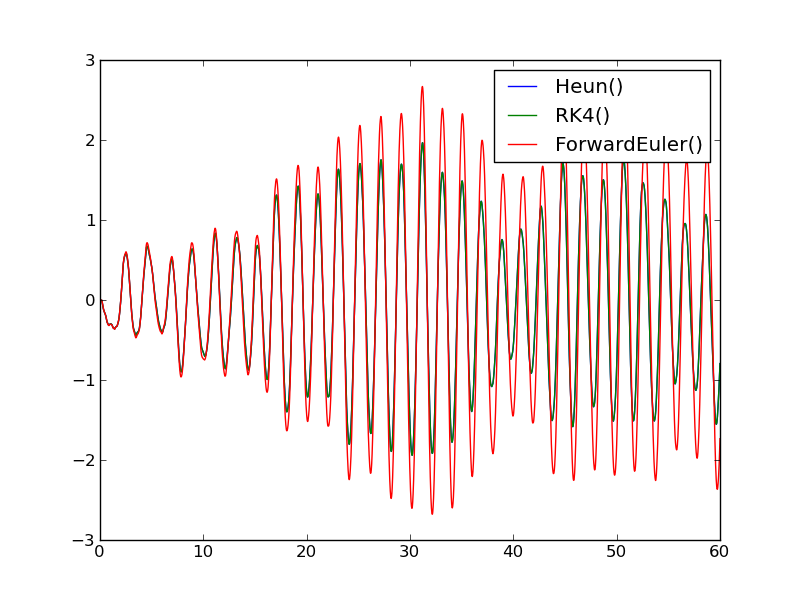

It is easy to compare different methods for solving this stochastic equation:

problem = WhiteNoiseOscillator(b=0.1, c=pi**2, sigma=1)

solvers = [odespy.Heun(problem.f), odespy.RK4(problem.f),

odespy.ForwardEuler(problem.f)]

for solver in solvers:

f.connect_solver(solver)

solver.set_initial_condition([0,0]) # start from rest

T = 60 # with c=pi**2, the period is 1

u, t = solver.solve(linspace(0, T, 10001))

x = u[:,0]

plot(t, x)

hold(True)

legend([str(s) for s in solvers])

All solutions are also stored in the solver objects as attributes u and t, so we may easily extract the solution of RK4 by

solvers[1].u, solvers[1].t

The Heun and RK2 methods give coinciding solutions while the ForwardEuler method gives too large amplitudes. The frequency is 0.5 (period 2) as expected.

In this example the white noise force is computed only once since the f instance is reused in all methods. If a new f is created for each method, it is crucial that the same seed of the random generator is used for all methods, so that the time evolution of the force is always the same - otherwise the solutions will be different.

The complete code is available in sode.py.

Adaptive Methods¶

The solvers used in the previous examples have all employed a constant time step \(\Delta t\). Many solvers available through the Odespy interface are adaptive in the sense that \(\Delta t\) is adjusted throughout the solution process to meet a prescribed tolerance for the estimated error.

Simple methods such as RK4 apply time steps

dt = time_points[k+1] - time_points[k]

while adaptive methods will use several (smaller) time steps than dt in each dt interval to ensure that the estimated numerical error is smaller than some prescribed tolerance. The estimated numerical error may be a rather crude quantitative measure of the true numerical error (which we do not know since the exact solution of the problem is in general not known).

Some adaptive solvers record the intermediate solutions in each dt interval in arrays self.u_all and self.t_all. Examples include RKFehlberg, Fehlberg, DormandPrince, CashKarp, and BogackiShampine. Other adaptive solvers (Vode, Lsode, Lsoda, RKC, RKF45, etc.) do not give access to intermediate solution steps between the user-given time points, specified in the solver.solve call, and then we only have access to the solution at the user-given time points as returned by this call. One can run if solver.has_u_t_all() to test if the solver.u_all and solver.t_all arrays are available. These are of interest to see how the adaptive strategy works between the user-specified time points.

The Test Problem¶

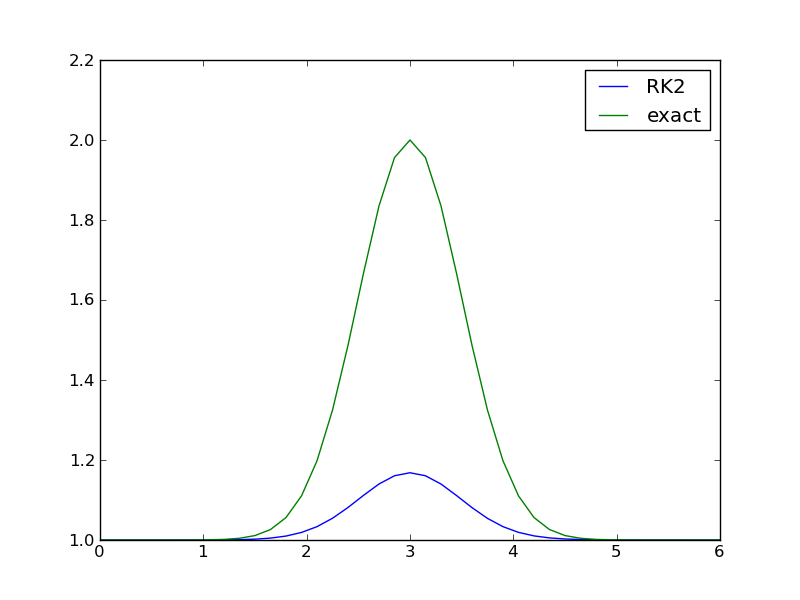

We consider the ODE problem for testing adaptive solvers:

The exact solution is a Gaussian function,

centered around \(t=c\) and width characteristic width (“standard deviation”) \(s\). The initial condition is taken as the exact \(u\) at \(t=0\).

Since the Gaussian function is significantly different from zero only in the interval \([c-3s, c+3s]\), one may expect that adaptive methods will efficiently take larger steps when \(u\) is almost constant and increase the resolution when \(u\) changes substantially in the vicinity of \(t=c\). We can test if this is the case with several solvers.

Running Simple Methods¶

Let us first use a simple standard method like the 2nd- and 4th-order Runge-Kutta methods with constant step size. With the former method (RK2), \(c=3\), \(s=0.5\), and \(41\) uniformly distributed points, the discrepancy between the numerical and exact solution in Figure 2nd-order Runge-Kutta method with 41 points is substantial. Increasing the number of points by a factor of 10 gives a solution much closer to the exact one, and switching to the 4th-order method (RK4) makes the curves visually coincide. The problem is therefore quite straightforward to solve using a sufficient number of points (400) and a higher-order method such as RK4. For curiosity we can mention that the ForwardEuler method produces a maximum value of 0.98 with 20,000 points and 0.998 with 200,000 points.

A simple program testing one numerical method goes as follows (gaussian1.py).

import odespy, numpy as np, matplotlib.pyplot as plt

center_point = 3

s = 0.5

problem = odespy.problems.Gaussian1(c=center_point, s=s)

npoints = 41

tp = np.linspace(0, 2*center_point, npoints)

method = odespy.RK2

solver = method(problem.f)

solver.set_initial_condition(problem.U0)

u, t = solver.solve(tp)

method = solver.__class__.__name__

print '%.4f %s' % (u.max(), method)

if solver.has_u_t_all():

plt.plot(solver.t_all, solver.u_all, 'bo',

tp, problem.u_exact(tp))

print '%s used %d steps (%d specified)' % \

(method, len(solver.u_all), len(tp))

else:

plt.plot(tp, solver.u, tp, problem.u_exact(tp))

plt.legend([method, 'exact'])

plt.savefig('tmppng'); plt.savefig('tmp.pdf')

plt.show()

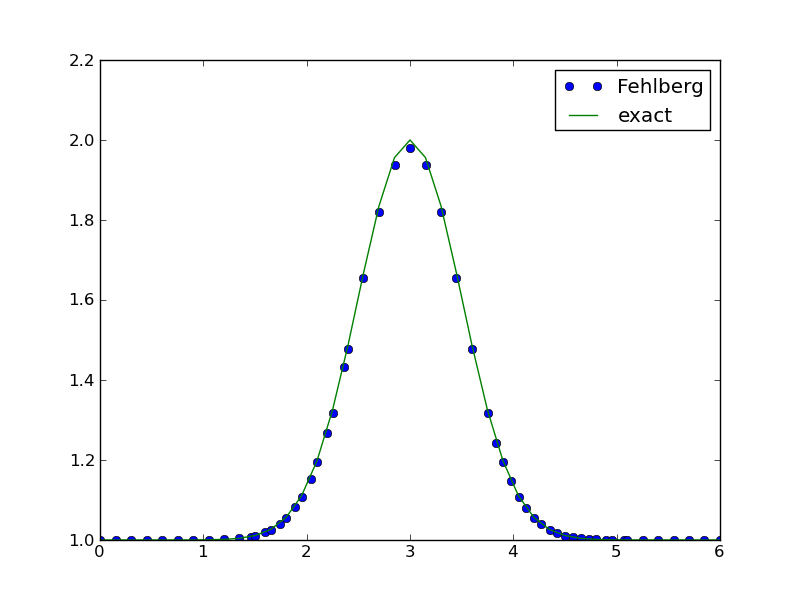

Running the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg Method¶

One of the most widely used general-purpose, adaptive methods for ODE problems is the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method of order (4,5). This method is available in three alternative implementations in Odespy: a direct Python version (RKFehlberg), a specialization of a generalized implementation of explicit adaptive Runge-Kutta methods (Fehlberg), and as a FORTRAN code (RKF45). We can try one of these,

method = odespy.Fehlberg

Figure Adaptive Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method with 57 points (starting with 41) shows how Fehlberg with 40 intervals produces a solution of reasonable accuracy. The dots show the actual computational points used by the algorithm (57 adaptively selected points in time).

Adaptive algorithms apply an error estimate based on considering a higher-order method as exact, in this case a method of order 5, and a method of lower order (here 4) as the numerically predicted solution. The user can specify an error tolerance. In the program above we just relied to the default tolerance, which can be printed by

print solver.get()

yielding a list of all optional parameters:

{'f_kwargs': {}, 'f_args': (),

'max_step': 1.5000000000000036, 'verbose': 0,

'min_step': 0.0014999999999999946,

'first_step': 0.14999999999999999,

'rtol': 1e-06, 'atol': 1e-08,

'name of f': 'f', 'complex_valued': False,

'disk_storage': False, 'u_exact': None}

The tolerances involved are of relative and absolute type, i.e.,

estimated_error <= tol = rtol*abs(u) + atol

is the typical test on whether the solution is sufficiently. For very small u, atol comes into play, while for large u, the relative tolerance rtol dominates.

In this particular example, running RK4 with 57 equally spaced points yields a maximum value of 1.95, while Fehlberg with 57 adaptively selected points results in 1.98. Note that the tolerances used are \(10^{-6}\) while the real error is of the order \(10^{-2}\).

We can specify stricter tolerances and also control the minimum allowed step size, min_step, which might be too large to achieve the desired error level (gaussian2.py):

rtol = 1E-12

atol = rtol

min_step = 0.000001

solver = odespy.Fehlberg(problem.f, atol=atol, rtol=rtol,

min_step=min_step)

The Fehlberg solver now applies 701 points and achieves a maximum value of 2.00005. However, RK4 with the same number of (equally spaced) points achieves the same accuracy and is much faster.

Testing More Adaptive Solvers¶

We have already solved (1) with sufficient accuracy, but let us see how other methods perform, as this will most likely result in a surprise. Below is a program (gaussian3.py) that compares several famous and widely used methods in the same plot.

import odespy, numpy as np, matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def run(problem, tp, solver):

method = solver.__class__.__name__

solver.set_initial_condition(problem.U0)

u, t = solver.solve(tp)

solver.u_max = u.max()

print '%.4f %s' % (solver.u_max, method)

if solver.has_u_t_all():

plt.plot(solver.t_all, solver.u_all)

print '%s used %d steps (%d specified)' % \

(method, len(solver.u_all), len(tp))

else:

plt.plot(solver.t, solver.u)

legend.append(method)

plt.hold('on')

rtol = 1E-6

atol = rtol

s = 0.5

npoints = 41

center_point = 3

problem = odespy.problems.Gaussian1(c=center_point, s=s)

tp = np.linspace(0, 2*center_point, npoints)

min_step = 0.0001

methods = ['DormandPrince', 'BogackiShampine',

'RKFehlberg', 'Vode', 'RKF45', 'Lsoda']

solvers = [eval('odespy.' + method)(

problem.f, atol=atol, rtol=rtol,

min_step=min_step)

for method in methods]

# Run Vode with implicit BDF method of order 5

solvers[1].set(adams_or_bdf='bdf', order=5, jac=problem.jac)

legend = []

for solver in solvers:

run(problem, tp, solver)

plt.plot(tp, problem.u_exact(tp))

legend.append('exact')

plt.legend(legend)

plt.savefig('tmp1.png')

# Plot errors

plt.figure()

exact = problem.u_exact(tp)

for solver in solvers:

plt.plot(tp, exact - solver.u)

plt.hold('on')

plt.legend(legend)

plt.savefig('tmp2.png')

plt.show()

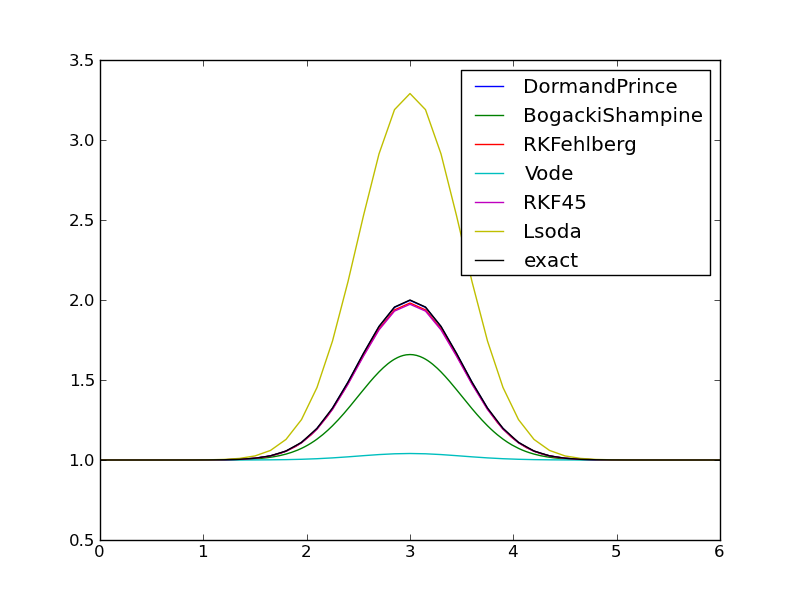

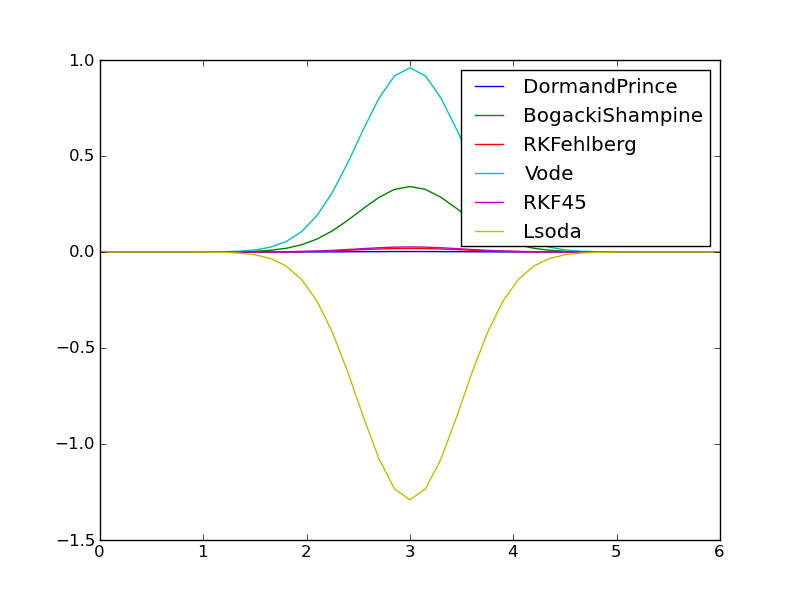

The default discretization applies \(N=40\) equal-sized time intervals, but adaptive methods should be able to adjust themselves to the desired error level \(10^{-6}\). Figures Comparison of adaptive methods with default parameters (tolerance ``E-6``) and Comparison of errors in adaptive methods with default parameters (tolerance ``E-6``) show that this expected behavior is not the case. There is substantial discrepancy between the methods! Surprisingly, the well-known FORTRAN codes accessed by the Vode (vode.f) and Lsoda (from ODEPACK) methods give very inaccurate results, despite setting Vode to use a stiff BDF solver of order 5, and Lsoda should automatically select between nonstiff and stiff solvers (of default order 4 in this case).

The program writes out the following results for the maximum value of the solution, which should equal 2:

1.9976 DormandPrince

1.6591 BogackiShampine

1.9812 RKFehlberg

1.0406 Vode

1.9734 RKF45

3.2905 Lsoda

The clearly most accurate solver among these is DormandPrince - the default method used by MATLAB’s ode45 solver, which is perhaps the world’s most popular ODE solver.

The remedy to get all the tested solvers to perform well is to choose a much stricter tolerance, say \(10^{-10}\). Figure Comparison of adaptive methods with error tolerance `E-10` shows coinciding curves. Numerically, we now have

1.9991 DormandPrince

1.9912 BogackiShampine

1.9942 RKFehlberg

2.0122 Vode

1.9916 RKF45

2.0056 Lsoda

For the methods DormandPrince, RKFehlberg, and BogackiShampine we have information about the number of adaptive time points used: 270, 326, and 3307, respectively.

The lesson learned in this example is two-fold: 1) several methods should be tested to gain reliability of the results, and Odespy makes such tests easy to conduct, and 2) strict tolerances, far below the default values, may be necessary for some methods, here Vode and Lsoda in particular. We remark that it is the ODE problem that causes difficulties: changing the problem to odespy.problems.Logistic (see the file logistic9.py) shows that all the curves coincide and cannot be distinguished visually.

The present test problem with a Gaussian function as solution can be made increasingly more difficult by increasing the value of \(c/s\), i.e., a more peaked function moved to the right.

Extensive Testing¶

The program gaussian4.py sets up an extensive experiments involving a lot of solvers, several \(c/s\) values, and several error tolerances. The experiments clearly demonstrate how challenging this ODE problem is for many adaptive solvers unless \(c/s\) is moderate and a strict tolerance (much lower than the real accuracy level) is used. One can especially see the fundamental difficulties that Vode, Lsode, and Lsoda (all stiff and nonstiff versions) face when \(c/s\geq 8\): these solvers do not manage to pick up any variation in \(u\). Nevertheless, for less demanding ODEs these solvers may perform very well, but it is highly recommended to always use the power of the unified Odespy interface to test several different adaptive methods.

Solving Partial Differential Equations¶

Let us now turn the attention to the method of lines for partial differential equations (PDEs) where one reduces a PDE to a system of ODE and then applies standard methods ODEs.

We address a diffusion problem in one dimension:

Discretization in Space¶

Discretizing the 2nd-order derivative in space with a finite difference, on a mesh \(x_i=i\Delta x\), \(i=1,\ldots,N-1\), gives the ODEs

Here we have introduced the notation \(u_i(t)\) as an approximation to the exact solution at mesh point \(x_i\).

The boundary condition on \(x=0\), \(u(0,t)=s(t)\), gives rise to the ODE

At the other end, \(x=L\), we use a centered difference approximation \((u_{N+1}(t)-u_{N-1}(t))/(2\Delta x) =0\) and combine it with the scheme for \(i=N\) to obtain the modified boundary ODE

To summarize, the ODE system reads

The initial conditions are

We can apply any method for systems of ODEs to solve (6)-(8).

Implementation¶

Consider the evolution of the temperature in a rod modeled by our diffusion problem. At \(t=0\), the rod has the temperature 10 C. We then apply a heat source at \(x=0\) which keepes the temperature there at 50 C. This means that \(I(x)=283\) K, except at the end point: \(I(0)=423\) K, \(s(t) = 423\) K, and \(f=0\).

Odespy solvers need the right-hand side function of (6)-(8):

def rhs(u, t, L=None, beta=None, x=None):

N = len(u) - 1

dx = x[1] - x[0]

rhs = zeros(N+1)

rhs[0] = dsdt(t)

for i in range(1, N):

rhs[i] = (beta/dx**2)*(u[i+1] - 2*u[i] + u[i-1]) + \

f(x[i], t)

rhs[N] = (beta/dx**2)*(2*u[i-1] - 2*u[i]) + f(x[N], t)

return rhs

This function requires the variables beta, x, dx, and L, which we provide as keyword arguments and that can be transferred to rhs through the f_kwargs argument to the Odespy constructors.

We also need some helper functions

def s(t):

return 423

def dsdt(t):

return 0

def f(x, t):

return 0

Parameters and initial conditions can be set as

N = 40

L = 1

x = linspace(0, L, N+1)

f_kwargs = dict(L=L, beta=1, x=x)

u = zeros(N+1)

U_0 = zeros(N+1)

U_0[0] = s(0)

U_0[1:] = 283

The construction and execution of a solver is now a matter of

import odespy

solver = odespy.ForwardEuler(rhs, f_kwargs=f_kwargs)

solver.set_initial_condition(U_0)

dx = x[1] - x[0]

dt = dx**2/(2*beta) # Forward Euler limit

N_t = int(round(T/float(dt)))

time_points = linspace(0, T, N_t+1)

u, t = solver.solve(time_points)

We can add some flexibility and set up several solvers, also implicit methods:

import odespy

solvers = {

'FE': odespy.ForwardEuler(

rhs, f_kwargs=f_kwargs),

'BE': odespy.BackwardEuler(

rhs, f_is_linear=True, jac=K,

f_kwargs=f_kwargs, jac_kwargs=f_kwargs),

'B2': odespy.Backward2Step(

rhs, f_is_linear=True, jac=K,

f_kwargs=f_kwargs, jac_kwargs=f_kwargs),

'theta': odespy.ThetaRule(

rhs, f_is_linear=True, jac=K, theta=0.5,

f_kwargs=f_kwargs, jac_kwargs=f_kwargs),

'RKF': odespy.RKFehlberg(

rhs, rtol=1E-6, atol=1E-8, f_kwargs=f_kwargs),

'RKC': odespy.RKC(

rhs, rtol=1E-6, atol=1E-8, f_kwargs=f_kwargs,

jac_constant=True),

}

try:

method = sys.argv[1]

dt = float(sys.argv[2])

T = float(sys.argv[3])

except IndexError:

method = 'FE'

dx = x[1] - x[0]

dt = dx**2/(2*beta) # Forward Euler limit

print 'Forward Euler stability limit:', dt

T = 1.2

solver = solvers[method]

The implicit solvers need the Jacobian of the right-hand side function:

def K(u, t, L=None, beta=None, x=None):

N = len(u) - 1

dx = x[1] - x[0]

K = zeros((N+1,N+1))

K[0,0] = 0

for i in range(1, N):

K[i,i-1] = beta/dx**2

K[i,i] = -2*beta/dx**2

K[i,i+1] = beta/dx**2

K[N,N-1] = (beta/dx**2)*2

K[N,N] = (beta/dx**2)*(-2)

return K

Note that we work with dense square matrices while the mathematics allows a tridiagonal matrix and corresponding solver. However, in 1D problems, the computations are so fast anyway so we can live with dense matrices.

Finally, some animation of the solution is desirable:

# Make movie

import os

os.system('rm tmp_*.png') # remove old plot files

plt.figure()

plt.ion()

y = u[0,:]

lines = plt.plot(x, y)

plt.axis([x[0], x[-1], 273, 1.2*s(0)])

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('u(x,t)')

counter = 0

for i in range(0, u.shape[0]):

print t[i]

lines[0].set_ydata(u[i,:])

plt.legend(['t=%.3f' % t[i]])

plt.draw()

if i % 5 == 0: # plot every 5 steps

plt.savefig('tmp_%04d.png' % counter)

counter += 1

#time.sleep(0.2)

Vectorized Code¶

It is easy to get rid of the loops in the rhs and K functions:

def rhs_vec(u, t, L=None, beta=None, x=None):

N = len(u) - 1

dx = x[1] - x[0]

rhs = zeros(N+1)

rhs[0] = dsdt(t)

rhs[1:N] = (beta/dx**2)*(u[2:N+1] - 2*u[1:N] + u[0:N-1]) + \

f(x[1:N], t)

i = N

rhs[i] = (beta/dx**2)*(2*u[i-1] - 2*u[i]) + f(x[N], t)

return rhs

def K_vec(u, t, L=None, beta=None, x=None):

"""Vectorized computation of K."""

N = len(u) - 1

dx = x[1] - x[0]

K = zeros((N+1,N+1))

K[0,0] = 0

K[1:N-1] = beta/dx**2

K[1:N] = -2*beta/dx**2

K[2:N+1] = beta/dx**2

K[N,N-1] = (beta/dx**2)*2

K[N,N] = (beta/dx**2)*(-2)

return K

Experiments¶

The program, pde_diffusion.py, can be run to test different solvers and illustrate numerical methods:

Forward Euler Method. Run

python pde_diffusion.py

The graphics takes very long time in this simulation, because of the small time step.

Backward Euler. Run

python ode_diffusion.py BE 0.05 1.2

Backward 2-step Method. Run

python ode_diffusion.py B2 0.05 1.2

Crank-Nicolson Method. Run

python ode_diffusion.py theta 0.01 1.2

Observe the non-physical oscillations because of the steep initial condition (and the lack of damping in the Crank-Nicolson scheme).

Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg Method. Run

python ode_diffusion.py RKF 0.01 1.2

Note here that we specify a quite large \(\Delta t\), much larger than what a Runge-Kutta method can work with (typically, an RK4 method needs a \(\Delta t\) as small as the critical step for the Forward Euler method). However, the adaptive method figures out what it needs of steps and produces a nice solution.

Runge-Kutta-Chebyshev Method. Run

python ode_diffusion.py RKC 0.05 1.2

This is a promising method for the diffusion equation. It works like an explicit method and can tolerate large time steps. This method calls up the FORTRAN code rkc.f.

Inner Workings of the Package¶

There are three basic entities when solving ODEs numerically: the definition of the ODE system, the time-stepping method, and the solver that runs the “time loop” and stores results.

The information about the ODE system is made very simple: the user provides 1) an object that can be called as a Python function f(u, t), and 2) an array or list with the initial values. Some users will store this information in their own data structures, e.g., a class.

The time-stepping method and the algorithm for calling the time-stepping are collected in a solver class. All the solver classes are related in a class hierarchy. Each solver class initialized by the right-hand side function (f) and an optional set of parameters for controlling various parts of the solution process. The solver object is also used to set the initial condition (set_initial_condition) and to run the solution process (solve). The time-stepping scheme is normally isolated in a method advance in the solver classes, but for some schemes or external software packages the separation of doing one step and doing the whole time integration is less feasible. In those cases, solve will mix the time-stepping loop and the numerical scheme.

The package does not interact with visualization tools - the array containing the solution is returned to the user and must be further processed and visualized in the user’s code.

Below we describe how the classes in the solver hierarchy work and how parameters are registered and initialized.

Solver Parameters¶

The solver module defines a global dictionary _parameters holding all legal parameters in Odespy classes. These are parameters that the user can adjust. Other modules imports this _parameters dict and updates it with their own additional parameters.

For each parameter the _parameters dict stores the parameter name, a default value, a description, the legal object type for the value of the parameter, and other quantities if needed. A typical example is

_parameters = dict(

...

f = dict(

help='Right-hand side f(u,t) defining the ODE',

type=callable),

f_kwargs = dict(

help='Extra keyword arguments to f: f(u, t, *f_args, **f_kwargs)',

type=dict,

default={}),

theta = dict(

help='eight in [0,1] used for'\

'"theta-rule" finite difference approx.',

default=0.5,

type=(int,float),

range=[0, 1])

...

}

Each solver class defines a (static) class variable _required_parameters for holding the names of all required parameters (in a list). In addition, each solver class defines another class variable _optional_parameters holding the names of all the optional parameters. The doc strings of the solver classes are automatically equipped with tables of required and optional parameters.

The optional parameters of a class consist of the optional parameters of the superclass and those specific to the class. The typical initialization of _optional_parameters goes like this:

class SomeMethod(ParentMethod):

_optional_parameters = ParentMethod._optional_parameters + \

['prm1', 'prm2', ...]

where prm1, prm2, etc. are names registered in the global _parameters dictionary.

From a user’s point of view, the parameters are set either at construction time or through the set function:

>>> from odespy import RK2

>>> def f(u, t, a, b=0):

... return a*u + b

...

>>> solver = RK2(f, f_kwargs=dict(b=1))

>>> solver.f_kwargs

{'b': 1}

>>> solver.set(f_args=(3,))